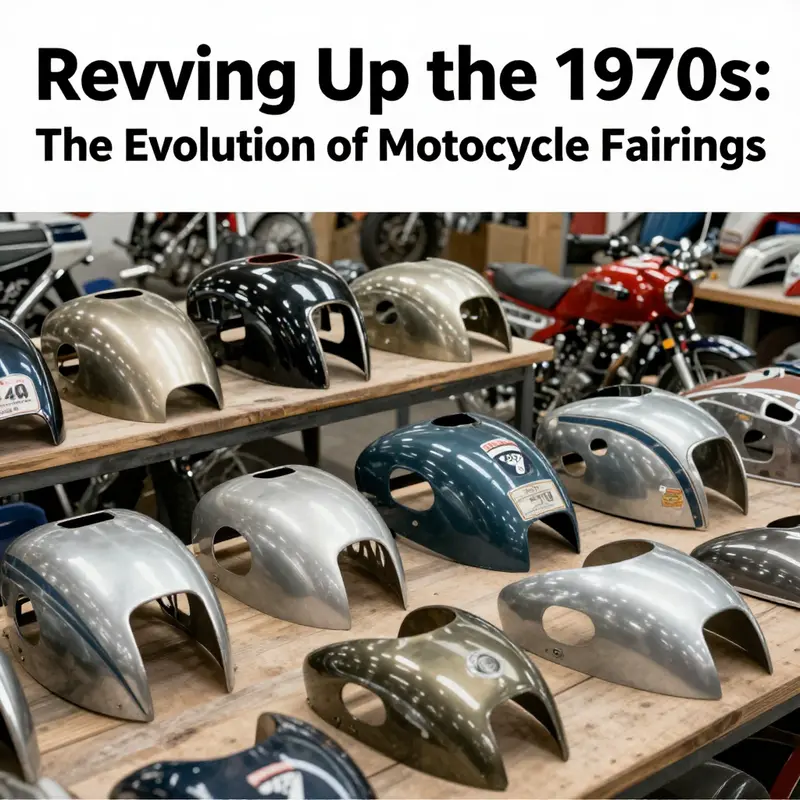

The 1970s marked a turning point in motorcycle design, particularly with the introduction and evolution of motorcycle fairings. These aerodynamic structures not only reshaped the aesthetic of bikes but also significantly enhanced performance and rider comfort. Business owners in the motorcycle industry can gain valuable insights by understanding the chapters that follow: the evolution of design and aesthetics, advancements in materials, the positive impact on performance and safety, cultural significance in the broader context of motorcycle history, and the current market trends surrounding these vintage components. Together, these insights form a comprehensive view of 1970s motorcycle fairings and their lasting legacy on today’s motorcycle landscape.

Winds of Change: Aerodynamics, Identity, and the Rise of 1970s Motorcycle Fairings

The 1970s did not merely introduce new plastics to motorcycle bodies; it signaled a shift in how riders felt about speed and endurance. Aerodynamics, once a whisper in wind tunnel reports and racing dreams, moved into the showroom and the road. Manufacturers imagined fairings not just as weather shields but as integral elements of motorcycle character. The shift was gradual, born from a collision of race technology and consumer desire for performance with everyday practicality. Early experiments were modest shells—lightweight, functional, and eager to shield the rider from gusts and fatigue. They spoke in fiberglass and molded plastic, with little concern for fashion and more for function: a smooth curve that reduced drag and a practical shape that could survive the bumps of daily riding. These beginnings planted the seed for a design language that would come to define an era, even as mechanics and metallurgy continued to evolve around the rider’s silhouette.

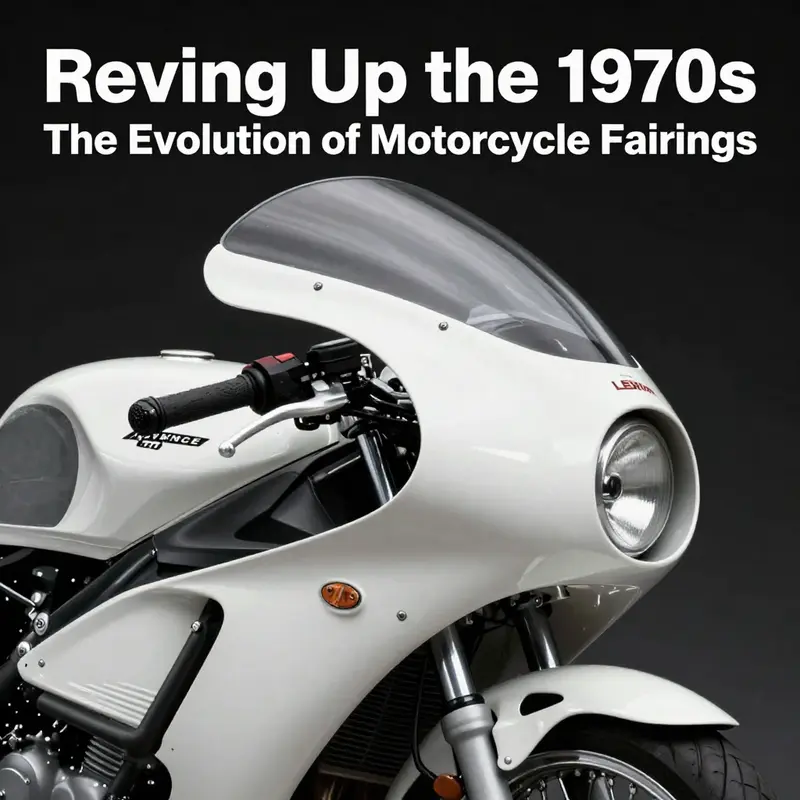

Yet the period’s competitive atmosphere pushed the design forward. As builders in different corners of the industry chased faster lap times, the fairings grew more sophisticated. Designers began to embrace streamlined silhouettes that wrapped around the front end and extended toward the sides, improving high-speed stability. The headlamp was no longer a separate feature but often housed within the fairing itself, a gesture toward integration that gave the bike a cohesive, race-inspired face. Contours became sculpted rather than simple shells; lines flowed into the handlebars and the lower fork area, guiding air to where it could do the most good. This was not only about speed; it was about a rider’s sense of confidence when cutting through air at speed, feeling the machine respond to the slightest input. The wind was no longer an adversary but a partner in performance, shaping how riders perceived ballast, balance, and resilience at speed.

Aesthetic transformation paralleled technical progress. The era’s sport bikes wore their speed as a visual signature: bold color schemes, gleaming chrome trim, and aggressive, futuristic lines. The fairing was no longer a mere accessory but a statement of identity. Designers used the growing toolkit of materials and shaping techniques to create a sense of motion even when the bike stood still. The goal was to imply velocity with every angle: a tapered nose, a tapered windscreen, and a protective shell that suggested aerodynamics in motion. In parallel, the broader market was excited by the idea of production-level engineering borrowed from racing. Consumers saw in these fairings a promise that everyday riding could feel closer to the track, a promise that helped convert performance into everyday appeal. The aesthetic shift was not simply about looking fast; it was about feeling fast, even when stuck in city traffic, a sensory cue that hinted at the machine’s true potential.

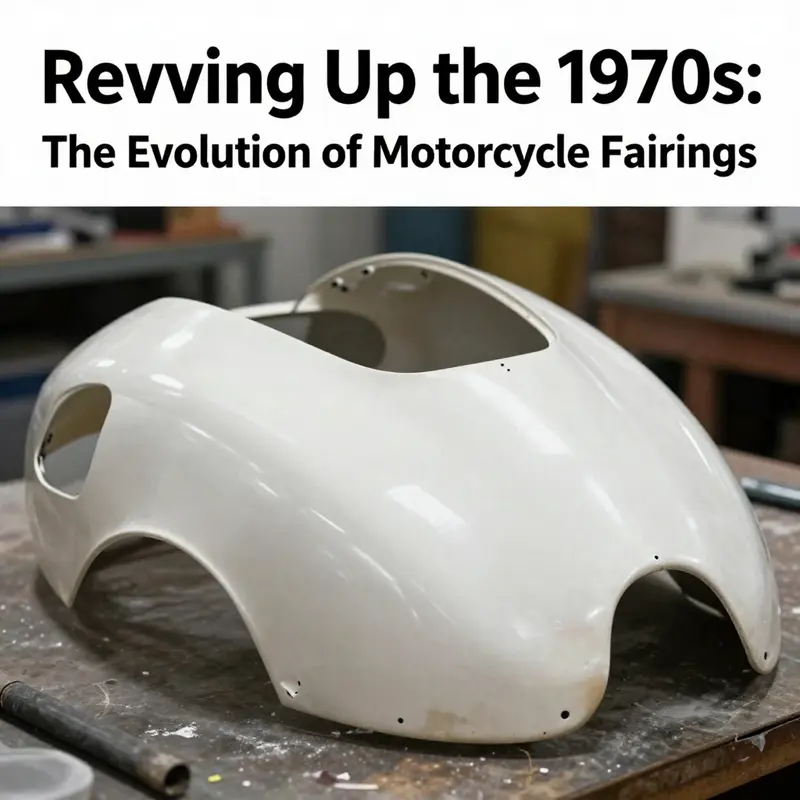

Manufacturing realities also shaped what appeared on the road. Early fairings were typically fiberglass or basic molded plastics, chosen for their lightness and relatively forgiving tooling. They were often heavier and less durable than later composites, and mounting systems were comparatively rudimentary. Small slips in alignment could dent a panel or loosen a seam, reminding riders that cutting-edge design demanded careful maintenance. Nevertheless, the benefits were tangible: the wind-induced drag dropped, and ride quality at highway speeds improved noticeably. The fairing transformed from a straightforward enclosure into a compact aerodynamic form, a living piece of design language that could change how riders experienced balance, comfort, and control when the speedometer crept into the upper ranges. As the decade progressed, manufacturers refined the process, experimenting with new laminates, joinery, and shell shapes that could better handle the stresses of real-world riding without sacrificing the lightness that performance demanded.

Behind the glossy shells, engineering teams experimented with how far the fairing could extend and what parts it could cradle. Integrated headlights were not just for fashion; they reduced glare and simplified the rider’s interface with instruments. Instrument clusters found themselves tucked into the fairing’s upper region, yielding a cleaner cockpit and a more compact silhouette. The fairing’s tail gathered air and provided some protection for the rider’s legs and knees, a design flourish that also helped the bike slice through gusts. This era’s designs still maintained a thoughtful balance between aerodynamics and practicality. The fairing’s size and shape had to work with real-world constraints—the bike’s weight distribution, the center of gravity, and the vulnerability of mounting points to the hazards of roads and weather. In the process, the fairing became a dynamic element of the bike’s overall geometry, not a separate skin slapped onto a chassis.

Within production lines, the fairing began to articulate what a motorcycle could be, beyond its engine displacement or chassis geometry. It became part of the machine’s storytelling. The mid-to-late 1970s saw a shift where producers began incorporating integrated fairings into more affordable models, extending the sportbike aesthetic beyond the limited realm of racing machines. This democratization of style helped broaden the market for sport-oriented riding, inviting a wider audience to experience the sense of speed and control these machines offered. The fairing ceased to be an optional add-on and became a signature element of a motorcycle’s identity. In the showroom, the shape could set the tone for a bike’s handling, its noise, and even its perceived value, because a well-executed fairing suggested a commitment to both performance and longevity. The design language of the era thus carried through to daily transportation, creating a legacy that would influence later generations of production models.

From a cultural perspective, the fairing’s evolution mirrored broader shifts in society’s relation to speed. The period’s graphics—shiny metal accents, bright colorways, and bold typography—reflected a public fascination with jets, racetracks, and the promise of mechanical precision. The fairing’s form and style invited personal expression; riders customized panels, swapped cores, and painted lines to echo their own sense of speed. In workshop conversations and showroom chatter, the fairing gained a personality, becoming something riders could identify with, something that spoke to a certain ethos of freedom and control. It was not just protection from wind; it was a medium for communicating where a rider stood on the spectrum between daily commuting and weekend track days. The fairing thus served as a cultural signpost, signaling not only technical prowess but a lifestyle choice that valued speed, engineering craft, and a kind of mechanical optimism about the future.

Maintenance and restoration presented both challenges and opportunities. Early fairings could be fragile, with composites that chipped or warped and mounting hardware that corroded or loosened over time. Restoration enthusiasts often sought original or period-accurate panels from vintage suppliers or specialized communities. Platforms and forums became valuable archives of historical context, guiding fans toward authentic pieces, correct mounting strategies, and period-appropriate finishes. The trade in such components and the knowledge to fit them properly created a micro-economy around the 1970s fairing aesthetic. The ongoing interest is not only nostalgia but a practical reminder of the era’s design language, where form and function intersected in a way that remains instructive for contemporary restoration projects. To collectors and historians, a fairing is more than a shell; it is a window into how people lived with speed, and how design disciplined the experience of riding through wind, weather, and time.

Scholarly work from design and manufacturing scholars has helped illuminate how these ideas traveled from race pits into street bikes. Recent analyses emphasize how advances in materials science and industrial standards, first tested during the 1970s, laid the groundwork for modern production practices. The story of the fairing thus becomes a case study in translating high-performance research into consumer products, shaping how designers approach wind resistance, cooling, and rider comfort in ways that still influence contemporary practice. In that sense, the fairing of the 1970s was not just a geographical or stylistic phenomenon; it was a vector for a broader shift in the relationship between machine, rider, and environment.

For readers tracing period-correct details or hunting for authentic restoration cues, period catalogs and dedicated communities remain invaluable. A useful way to explore period-appropriate branding and assembly is to consult dedicated collections and online marketplaces that specialize in classic components. If you are curious about the range of period fairings available for a particular brand, you can explore the Kawasaki fairings collection for context and options. Kawasaki fairings collection.

Further reading and broader context can be found in studies that examine the industrial and material innovations behind fairing design. For a deeper, cross-cultural perspective on how fairings intersect with manufacturing standards and the evolution of composite materials, see the external resource: Understanding Chinese Motorcycle Fairings: Composition, Standards, and Industrial Benefits.

From Canvas to Composite: 1970s Motorcycle Fairing Material Breakthrough

The 1970s marked a material turning point for motorcycle fairings, moving away from canvas and simple sheet metal toward molded plastics and fiberglass composites. Early efforts focused on protection and weather sealing, but as performance riding grew, designers sought shapes that reduced drag without sacrificing strength or ease of maintenance. Plastics offered continuity of curves and lower density, letting designers create enclosed profiles that metal could not easily reproduce. The lighter components also improved suspension and handling, tipping the balance toward performance integration.

Fiberglass composites expanded the toolbox further. By controlling layups, resin systems, and weave patterns, engineers could tailor stiffness, impact resistance, and weight distribution to specific regions of the fairing. This enabled smoother air flow, better rider comfort, and a more cohesive front-end appearance that signaled modern sportbike aesthetics.

Production realities followed: repeatable molding, color stability, and reliable mounting systems became as important as the shapes themselves. The new materials demanded new manufacturing habits, curing controls, and maintenance practices, but they paid off in lighter, stronger, and more integrated shells that defined the look and feel of 1970s performance motorcycles.

Culturally, the shift toward advanced materials transformed rider expectations. The fairing moved from a functional accessory to an aerodynamic interface between rider and machine, shaping ergonomics, cockpit layout, and the perceived speed of the bike, even when stationary. Enthusiasts and technicians learned to evaluate, repair, and replace composite skins, making serviceability a key part of the design language.

Wind, Speed, and Shield: How 1970s Motorcycle Fairings Redefined Performance and Rider Safety

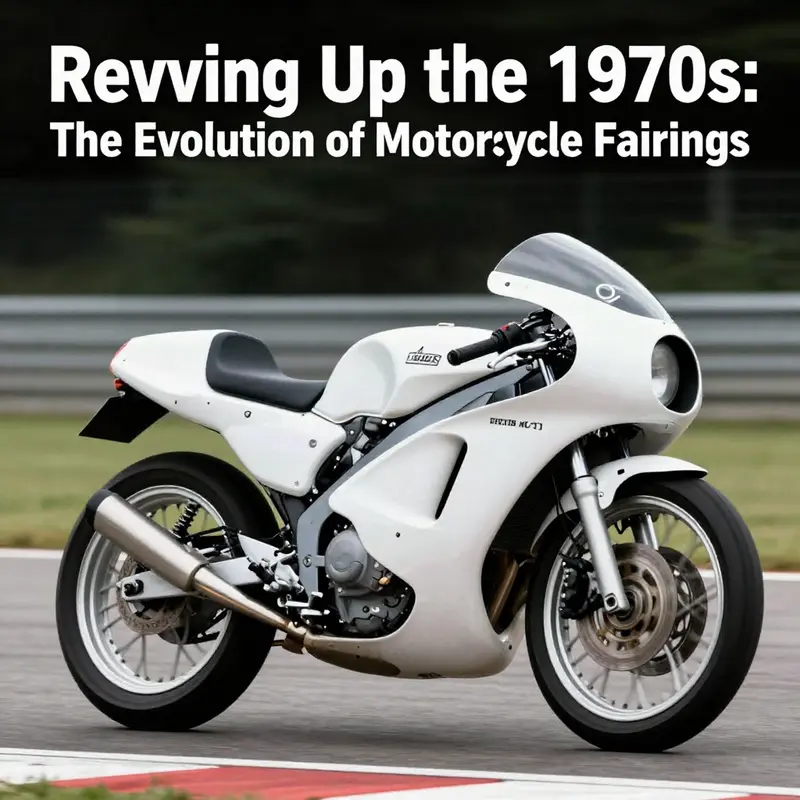

Wind is not merely a backdrop on the open road; in the 1970s it became a design force that challenged engineers to rethink what a motorcycle could become. This was a decade when aerodynamics moved from the periphery of racing imagination to the core of production philosophy. Fairings—once rare, utilitarian appendages—began to claim space in the wind tunnel, in the shop, and on the showroom floor. They were born out of a concise goal: to reduce wind resistance while offering the rider a more manageable and less exhausting ride. The materials favored for these shells—fiberglass and early molded plastics—were chosen for their ability to be shaped with relative ease and at a cost that made mass production feasible. The earliest fairings tended to be modest in scale, often enclosing the headlight and instrument cluster and following the upper contours of the fork. They offered a practical increment in aerodynamics without sacrificing the bike’s accessibility or serviceability. The result was a new category of motorcycle that could carry a rider farther, faster, with a bit less fatigue, and with the confidence that came from a more enclosed, streamlined silhouette.

As the decade progressed, the shapes grew more assertive. Designers learned that the front fairing was not merely a cosmetic garnish but a primary instrument in shaping the bike’s entire aerodynamic profile. A few mid- to late-70s machines demonstrated how a single shell could sweep from the front wheel to the engine bay, creating a cohesive, wind-deflecting skin. These full fairings did more than signify modernity; they redirected air around the rider and the machine as a single system. The ride felt smoother, the illusion of speed sharpened, and the potential for improved high-speed stability increased. Yet even at this stage, the fairings remained lean by contemporary standards. They often preserved open spaces for a headlight, a compact cluster of gauges, and a slender upper-fork arrangement, while the fairing’s chin or lower edge would tuck under the tank’s line and meet the frame with a measured elegance. This balance—clarity of form, ease of maintenance, and a clear aerodynamic objective—defined the era’s approach to fairing design and how riders would come to perceive speed.

The performance dividend was real, though bounded by era-specific realities. A fairing that reduced drag could shave a few tenths of a second off a lap time or enable a modest increase in top speed on a straightaway. More appreciable, though perhaps undervalued in some recaps, was the improvement in rider comfort. With less wind blasting the chest and shoulders, the rider could handle longer distances with reduced fatigue, a factor that mattered in endurance rides and long commuting days alike. The fuel economy story followed, especially at sustained highway cruising, where a cleaner flow around the bike could translate into a more efficient relationship between throttle input and air resistance. These benefits were inseparable from the fairing’s other role: signaling that speed and sophistication could coexist with practicality. The aesthetic impact was unmistakable as well. A full fairing didn’t simply clothe a mechanical silhouette; it declared the sport bike’s intent and set a tone for the visual language that defined the decade’s motorcycles. The shell’s lines, its intersections with the tank, and the way the wind seemed to bend around the rider all contributed to an image that suggested control and precision on every road and circuit.

For those who study restoration or who recreate period accuracy, the fairing is not just a shell but a record of a particular engineering moment. Sourcing authentic components can be part of the project’s appeal, and the restoration path often doubles as a study in how to adapt a shell to a current bike without losing the period’s look and feel. A practical starting point is to explore vintage suppliers and specialized forums where measurements, mounting points, and historical configurations are discussed in depth. For those seeking a tangible touchpoint during research, the Honda fairings collection offers a window into how these shapes evolved, how they integrated with tank geometry, and how fittings and stay points varied over the era. This kind of resource helps a restorer understand not just what the shell looked like, but how it attached, how it withstood vibration, and how it spoke to the bike’s overall chassis geometry. The period’s practice favored modularity: a fairing that could be slid into place over a set of brackets, with fasteners that could be tightened on a Saturday afternoon without specialized equipment. The result is a historical texture: a shell that looks the part, but also a document of the era’s mounting standards, tolerances, and the practical constraints of mass production.

In the broader design dialogue, the 1970s fairings also intersected with safety in ways that modern readers may find instructive. Helmets of the era varied widely in protection and construction. Some provided robust shell structures and active energy absorption; others offered less. The fairing’s primary safety impact was indirect. By shaping the airflow around the rider’s head and upper body, the fairing could influence the forces transmitted through the neck and upper spine during aggressive maneuvers or unexpected gusts. It did not, however, replace the helmet’s protective role, and the era’s safety culture lagged behind today’s standards in terms of crash protection and energy management. This is not to diminish the fairing’s contribution to rider confidence at speed; it simply situates the innovation within a safety framework that was still evolving toward the integrated protective systems we now take for granted. The takeaway is clear: the fairing helped manage wind and vibration, which indirectly supported safer riding by reducing rider fatigue and preserving control, while helmet technology and protective standards pursued their own parallel improvements.

Alongside these performance and safety considerations, the 1970s fairings reveal a pragmatic engineering mindset. The materials—glass-reinforced composites and early thermoplastics—carried advantages and drawbacks. They could be shaped with relative ease and produced in volume, yet they also carried exposure to impact damage and aging that later composites would better resist. The mounting hardware and the shell’s attachment points were not always engineered for the long tail of a bike’s life; this sometimes meant maintenance challenges or a greater risk of fairing distress after a harsh impact with road debris or a curb strike. Nevertheless, these challenges did not suppress a bold design impulse. The fairing became a canvas for the sportbike’s aggressive, forward-leaning posture and for the idea that a motorcycle could achieve both speed and drama through aerodynamic discipline. The form began to mirror the function, and a bike that once looked like a naked, mechanical argument transformed into a machine whose silhouette announced its aerodynamic intent before a rider even sat down.

The cultural footprint of the era’s fairings extends into today’s collector culture. Enthusiasts gather not only to ride but to understand a bike’s wind-sculpted history—the way a shell’s curvature interacts with a frame’s rake and trail, the nuance of a mounting stay that survives decades, and the way a small vent near the headlight could influence engine cooling on a hot day. In this sense, the fairing’s significance goes beyond its immediate performance gains. It codified a design language that remains audible in the lines of modern sportbikes, even as construction technologies have evolved. The 1970s marked a transition from purely functional shells to visually coherent aerodynamic bodies that married speed with style, a synthesis that would define the sportbike aesthetic for years to come.

All of this is intimate with the way the market works today. Restorers and collectors rely on a supply chain that includes vintage suppliers, online marketplaces, and specialized communities where owners trade techniques, measurements, and war stories about a shell’s fitment. Through these channels, period accuracy can be preserved, and new generations can engage with the era’s design vocabulary. The fairing’s story is, ultimately, a story about how a technical challenge—wind—can drive a cultural and aesthetic shift that reshapes how a motorcycle looks, feels, and performs. It is a reminder that the pursuit of speed is as much about the air we move through as the power we unleash. The wind, once a stubborn opponent, became a partner in design, guiding the evolution of a machine that would forever be associated with a bold, wind-cutting future that began in the 1970s.

External reference: For a broader context on how fairings affect performance and safety, see BikeRadar’s analysis at https://www.bikeradar.com/uk/motorcycles/gear-and-accessories/motorcycle-fairings-how-they-improve-performance-and-safety/)

Wind, Velocity, and Identity: The Cultural Significance of 1970s Motorcycle Fairings

The 1970s arrived with a particular urgency for motorcycles and their riders. Wind, engine, and road fused into a vocabulary of speed that felt almost new to a generation eager to redefine risk, rebellion, and personal style on two wheels. In this moment, fairings ceased to be simple shieldings from the elements and became radical statements about what motorcycles could be. They carried aerodynamic logic into living rooms and roadways alike, translating complex airflows into lines and curves people could recognize, imitate, and, crucially, aspire to. The cultural significance of those fairings rests not only in the way they cut drag or shield the rider from buffeting but in how they reframed the motorcycle as a complete, integrated idea. A bike was no longer just an engine with wheels; it was a streamlined argument about speed, control, and modern identity.

In the earlier chapters of design, fairings were practical experiments: fiberglass shells lightly molded to cover a headlight and a fork crown, a practical solution for wind at modest speeds and limited by the materials and tooling of the time. Yet the 1970s accelerated the evolution from utilitarian appendage to integrated feature. The period’s most iconic examples illuminate this shift. The Norton Commando SS of 1974 stands as a landmark, with a full fairing that enveloped the front end, creating a silhouette that read as much like a cockpit as a motorcycle. It whispered of racebred efficiency while projecting a confident, almost defiant, street presence. The full fairing offered tangible benefits—reduced wind pressure on the rider, improved stability at higher speeds, and a visual language that suggested advanced engineering—yet its impact went deeper. It signaled the rider’s readiness to embrace speed as a lifestyle, not merely a hobby, and it invited spectators to read a motorcycle as a commitment to modernity rather than a nostalgic relic.

Alongside Norton’s bold approach, the late 1970s brought production bikes with more deliberate, integrated fairing design. The Honda CB750 Four, introduced around 1978, became a watershed model for turning aerodynamic ambition into mass-market reality. Its fairing strategy, while not as enveloping as some pure racing machines, demonstrated the practical elegance of an integrated design. It fused the headlight, cockpit, and upper fairing into one coherent front end, creating a visual grammar that future sportbikes would hinge upon. This convergence of function and form helped to normalize the idea that a motorcycle’s aesthetic could be inseparable from its engineering—an aesthetic that carried with it promises of comfort on longer rides, steadier stability at speed, and a sense of belonging to a progressive, forward-looking community of riders.

What made these fairings culturally meaningful went beyond mere performance numbers. They reflected a broader cultural movement that equated speed with modern self-expression. The fairing was a symbol of possibility—the possibility that technology could be tamed, shaped, and worn as a statement of taste and daring. In the 1970s imagination, a sleek, streamlined bike invited young riders to imagine themselves as part of an elite circle of racers and technically minded enthusiasts. The lines of the fairings—clean, purposeful, sometimes aggressively angular or subtly curving—became a visual shorthand for a phase when youth culture embraced technology as a countercultural ally. A rider with a fairing was signaling a break from prewar or postwar conventions and claiming a new vernacular of speed.

This cultural moment was inseparable from the industry’s broader shifts in production philosophy. Aerodynamics moved from late-20th-century curiosity into a practical design discipline that influenced every major manufacturer, even as it remained accessible to enthusiasts who would later restore or recreate period-correct machines. The shape of a fairing often carried a narrative about who the bike was for and what it promised to deliver. A fairing suggested long, wind-influenced journeys as equally as it suggested short, wind-tweaked sprints. It was about comfort on a ride, yes, but also about confidence—an aura of control that allowed riders to push toward the horizon rather than recoil from it. In that sense, the 1970s fairing contributed to shaping the sportbike ethos that endures today: speed balanced with endurance, performance coupled with rider protection, and a shared visual identity that transcends one model or era.

Within this cultural frame, the fairing became a connector between racing innovation and street accessibility. Manufacturers began to see aerodynamics not only as a way to win races but as a way to broaden the appeal of sport-oriented motorcycles to a wider audience. The transition from fiberglass and rudimentary plastics to more sophisticated, integrated fairings reflected this broader democratization. It offered a sense that cutting-edge engineering could be affordable and achievable for enthusiastic riders, not just for factory teams. The look of the period—long, smooth profile lines; a front end that married function to now-familiar sportbike aesthetics—gave rise to a visual identity that would be recognized in countless later models, across brands and continents. Even as certain materials and mounting systems proved less durable than those of modern components, the spirit of experimentation—the willingness to shape air as a partner rather than a nuisance—became part of the culture of motorcycling itself.

From a historical vantage point, the 1970s fairings did more than reduce drag or improve rider comfort. They coalesced performance engineering with a cultural longing for speed and personal expression. They helped turn motorcycles into symbols of youth, ingenuity, and the belief that a two-wheeled machine could be both highly functional and strikingly stylish. The fairing’s trajectory—from a functional shield to a defining aesthetic element—echoed a broader shift in how people related to technology. It invited riders to regard their machines as extensions of their personalities, as much as tools for transportation. And while the riding experience in the era was undeniably shaped by the practical realities of the time—period-specific materials, mounting methods, and the evolving standards of durability—the cultural imprint endures in the language of design that continues to inform contemporary sportbikes.

For readers who seek to understand the continuity between early fairing experiments and later production innovations, it is instructive to consider how subsequent generations of bikes drew on these foundations. The fairing’s purpose expanded as manufacturers refined their approach to aerodynamics and rider comfort, turning the concept into a durable, recognizable element of a motorcycle’s identity. This lineage—where form follows function yet still carries a distinct sense of place and time—helps explain why the 1970s remain a touchstone in discussions of motorcycle design. The era’s fairings did not merely improve performance; they crystallized a vision of motorcycling as a space where engineering prowess and personal style cohabit, where the rider and the machine share a common destiny on the open road.

For readers who wish to explore period styling or seek authentic reference points for restoration, the continuity between historic design and modern re-creations is instructive. As a practical resource, enthusiasts often turn to dedicated collections that showcase era-specific shapes, mounting schemes, and finish options. One useful point of reference in this regard is the Kawasaki fairings collection, which offers a window into how such shapes have endured as a core element of the sportbike silhouette. Kawasaki fairings collection. By studying these collections, restorers and designers can gain insight into the lineage of lines, the cadence of curves, and the evolving vocabulary of fairing aesthetics that began in earnest in the 1970s and continued to inform subsequent decades.

External resource: What Were Popular 1970 Motorcycle Models in the US? A Guide. https://www.motorcycle.com/1970-motorcycle-models-us-guide/

Riding the Edge of Time: Market Trends, Provenance, and Collectability of 1970s Motorcycle Fairings

Across the arc of the 1970s, motorcycle fairings moved from practical wind protection toward a more expressive intersection of performance, style, and identity. The shift was as much about the rider experience as about the machine’s physiology. Aerodynamics mattered not only to top speed and stability but to the everyday comfort of riding at speed or in gusty crosswinds. In this chapter, we trace how those pioneering fairings emerged from simple, utilitarian shells to become coveted relics that signal a particular moment in motorcycling history. The market that now valorizes these pieces reflects both the romance of the era and the practicalities of restoration and preservation. Buyers today are not merely looking for a replica of a curved panel; they seek a connection to a period when engineering and aesthetics began to fuse in bold, sometimes flamboyant expressions that matched the racing and touring ambitions of the day. The appeal rests on the fairing’s ability to tell a story about speed, tension, and the evolving relationship between rider and machine. The 1970s were a proving ground where fiberglass and molded plastics demonstrated new possibilities, and the first widely adopted full or semi integrated fairings appeared in production bikes that could still be found on showroom floors and, increasingly, in the hands of collectors who prize authenticity above novelty. These early shells often covered only the headlight and upper fork area, a pragmatic compromise between aerodynamics and accessibility for maintenance. Yet even in that restraint you can sense a turning point: a deliberate move away from purely mechanical form toward a more holistic silhouette that integrated bodywork with engine and chassis geometry. The result was a design language that would define the sportbike aesthetic for a generation and a market that now treats any surviving shell as a historical artifact in its own right. In markets around the world, the story of these fairings is closely tied to national design cultures and the shifting economics of motorcycle production during the late 70s. In Japan, for instance, a custom and street-culture sensibility flourished around highly styled, sometimes extravagant fairings that became symbols of a broader automotive and design revolution. While these custom pieces might have hovered on the edge of mass production, their influence rippled outward, shaping what enthusiasts today recognize as period-correct styling cues and the expectations attached to originality. The bōsōzoku ethos, with its bold color choices and intricate detailing, has become part of the historical fabric that informs collectors’ judgments about what constitutes authentic presentation from the era. Such cultural modules matter because collectability is not merely about an item’s physical condition; it is about provenance, context, and the ability of a single shell to anchor a broader historical narrative. In Western markets, the late 70s saw Japanese manufacturers push into production with fairings that balanced wind tunnel insight with rider comfort. Those first integrated approaches helped popularize a modern sportbike silhouette that many builders would later emulate across decades. The fairings themselves, often cast in fiberglass or molded plastics, varied in thickness, finish, and mounting systems. They could be surprisingly fragile by today’s standards, and that fragility adds to their story. A dented revival shell may still carry more historical weight than a pristine, reproduction piece, precisely because it bears the signs of hands that tested it on damp road reveals and race tracks alike. Because authenticity is the currency of the current market, the provenance of a fairing becomes a central criterion for value. Documentation that traces a shell back to a specific model year, a known race or touring configuration, or a documented restoration adds substantial credibility and can lift a fairing from rare to collectible. In practice, collectors and restorers weigh several factors when evaluating value. The first is authenticity: whether the fairing is original to a particular machine or, if a replacement, whether it is period-correct and true to the era’s construction methods. The second is condition: the extent of cracks, warping, or delamination, and the quality of any repairs. Original finishes, even if weathered, can carry more weight than a perfectly repainted shell because they preserve the fairing’s patina and lie closer to the machine’s lived history. The third is provenance: a clear record of ownership, assembly, and installation that can authenticate the shell’s journey from factory, to race paddock, to roadside, and finally to a collector’s shelf. These dimensions—authenticity, condition, and provenance—function as a triad that governs market behavior, influencing both the price and the collector’s confidence in a purchase. Yet the story of 1970s fairings is not only about the pieces themselves. The aftermarket has become a crucial force in shaping market dynamics. A robust ecosystem of reproductions and high-quality aftermarket shells has emerged, offering durable materials such as ABS that preserve the original look while providing greater resilience than some early fiberglass variants. This development has broad implications: it makes it possible for a wider range of enthusiasts to restore or update a vintage machine without compromising on overall aesthetics or structural integrity. When a restoration project seeks period-appropriate lines and finish, the availability of credible aftermarket parts lowers the barrier to completion and keeps the historical narrative accessible. At the same time, the presence of reproductions subtly recalibrates valuation. While originals still command premium when provenance and condition align, well-executed reproductions can preserve the look and feel of the era, enabling more bikes to maintain roadworthiness and display value within a living subculture rather than becoming museum pieces that never hit the road. For true connoisseurs, however, the original piece remains the apex of collectability. The advantage lies less in the shell’s ability to protect the rider from wind and weather than in the shell’s capacity to tell a story about a moment when design risk and engineering curiosity aligned to create something both functional and aspirational. This is where fairings transcend their physical utility and become signifiers of an era’s appetite for speed and style. The market for these components, accordingly, bears the imprint of global collecting trends. Japanese influence, with its emphasis on bold customization and highly visible detailing, has established a baseline expectation for originality and presentation that collectors use when evaluating candidates for purchase. In Western markets, the renewed attention to historical context and engineering heritage has elevated the status of 1970s fairings as credible, not merely decorative, artifacts. The net effect is a steadily rising interest in authentic pieces, even as the aftermarket scene provides practical pathways for preservation and display. For those seeking to engage with this market thoughtfully, a careful balance of research, condition assessment, and a clear sense of provenance is essential. Enthusiasts increasingly rely on shared knowledge through forums, restoration guides, and curated catalogs that help verify what constitutes period-correct fitment and what counts as a permissible reproduction. This communal knowledge supports a healthier, more transparent market where buyers can weigh the risks of buying a shell with incomplete history against the satisfaction of completing a historically faithful bike project. The future outlook remains positive for collectors who approach the landscape with patience and diligence. As interest in 1970s motorcycles continues to rise, producers and restorers are likely to invest in more accurate reproductions and more rigorous documentation practices. The result could be a broader ecosystem that maintains the authenticity of the era while expanding accessibility for new generations of riders and restorers. As vintage motorcycle culture grows, fairings will continue to be celebrated not just for their aerodynamic function but for their capacity to anchor a community’s shared memory of speed, risk, and the thrill of carving a line through wind on a summer road. For those who want to explore period-accurate pieces or source restoration parts, a wide range of options remains available, and the community continues to provide education about what to seek and how to verify authenticity. A collector might turn to a trusted catalog or marketplace to locate original shells or reliable reproductions, guided by an understanding of the era’s design language and the machine’s engineering lineage. For enthusiasts considering a focused purchase, the journey begins with a clear sense of what the fairing represents—how it integrates with the machine’s chassis, how its lines speak to the rider’s posture, and how its finish communicates the era’s aesthetics. It is a reminder that the fairing is not merely a protective shell but a compact sculpture in which performance, culture, and memory converge. To explore options and learn more about period-appropriate pieces and their sourcing, see the Honda fairings collection for a sense of how contemporary restorers approach the task and how the lineage of design continues to influence the market today that connects back to the original era. Honda fairings collection. As you widen your understanding, you may also consult broader industry histories and restoration resources that contextualize how these shells shaped the era’s riding experience and why they command attention among collectors today. For deeper context on vintage motorcycle history and restoration tips, see Classic Motorcycle. (External resource: https://www.classicmotorcycle.com/)

Final thoughts

The analysis of 1970s motorcycle fairings uncovers profound insights into not only how they transformed bike design but also how they’ve shaped the culture surrounding motorcycles. Understanding these elements can help business owners harness the nostalgia and technical advancements of this era to better connect with modern enthusiasts. The legacy of 1970s fairings is not just about style; it speaks to an enduring passion for performance and community in motorcycling.