As the automotive and motorsport industries embrace the potential of advanced manufacturing technologies, 3D printed motorcycle fairings emerge as a groundbreaking development. These lightweight, customizable body panels have revolutionized motorcycle design, offering improved aerodynamics and performance efficiencies. For business owners, understanding the technology, design innovations, material science, and market trends surrounding 3D printed fairings can reveal untapped opportunities to enhance product offerings and cater to a growing niche in the motorcycle market. Each chapter delves into critical aspects that underpin this innovative approach, equipping decision-makers to leverage these advancements for competitive advantage.

Layered Velocity: The Engineering Narrative Behind 3D-Printed Motorcycle Fairings

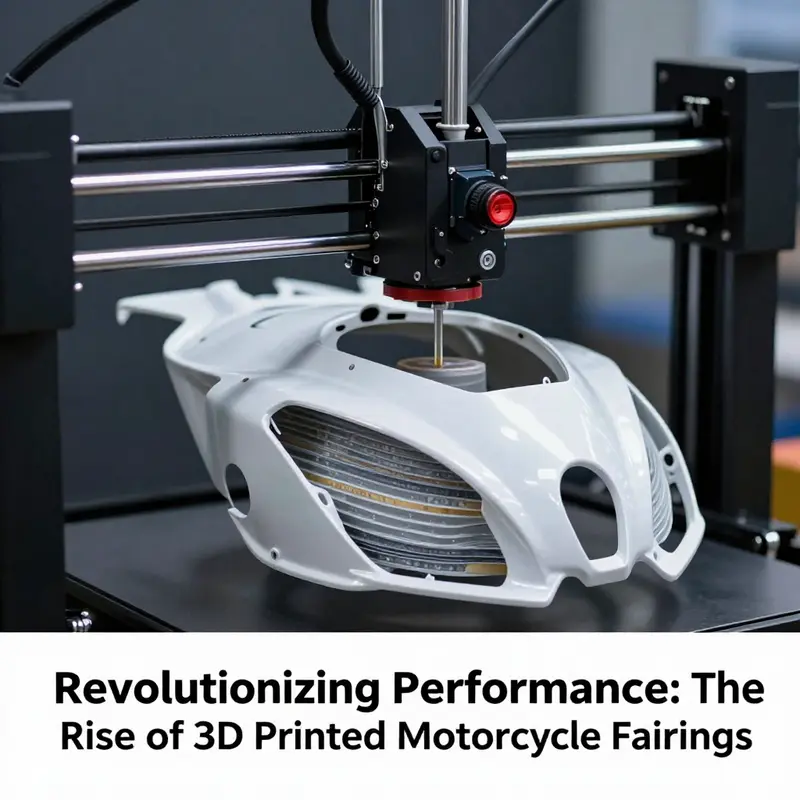

Three words describe the turn toward 3D-printed motorcycle fairings: design freedom, material science, and rapid iteration. In a field where the shape of a bike’s skin can determine stability at speed, the shift from carved molds to additive manufacture marks more than a change in tools; it signals a shift in how engineers think about performance, integration, and how riders experience the machine itself. The technology sits at the intersection of aerodynamics, structural engineering, and customized aesthetics, and it does so with a fluency that traditional processes struggle to match. At its core, 3D printing builds parts layer by layer from digital models, allowing a level of precision and complexity that was once prohibitively expensive or physically impossible. Where conventional methods require costly tooling, long lead times, and compromises born from mold limitations, additive manufacturing opens a design space that can be explored, tested, and refined in a fraction of the time. The result is fairings that can be lighter, stronger, and more aerodynamically efficient while still fitting a bike’s geometry with exacting tolerances and repeatable quality. This fusion of capabilities is not merely about lighter panels; it is about rethinking how air, heat, and impact interact with the rider and the motorcycle’s core structure, all while supporting the evolving demands of racing, customization, and sustainability. The conversation about 3D printed fairings begins with process. When a part is built additively, it is not sliced from a single block of material but conceived as a sequence of layers that come together to form a functional whole. This layer-by-layer approach enables designers to embed features that would be difficult or costly to machine from solid stock or to cast within a standard mold. Complex internal pathways, lightweight lattice lattices, and hollow structures can be integrated seamlessly into a single part, reducing weight without sacrificing stiffness and allowing the part to carry loads in more efficient ways. The ability to tailor internal geometries is more than an engineering curiosity; it directly translates into better handling characteristics. A well-optimized fairing can manage wake flow behind the rider, shaping pressure distributions to minimize drag and to stabilize the motorcycle at high speeds, where even small improvements in aerodynamics yield meaningful gains in acceleration, top speed, and fuel efficiency. The design language of these parts embraces this complexity rather than fearing it, treating every curve, rib, and lattice node as a tool for performance rather than a merely aesthetic flourish. The materials chosen for these parts reinforce this philosophy. Thermoplastics such as ABS, ASA, and polycarbonate are often the workhorses in early-stage, rapid-prototyping applications due to their balance of toughness, heat resistance, and printability. ABS offers toughness and machinability, making it a reliable choice for concept validation and functional testing. ASA adds improved weather resistance and UV stability, helping parts endure sunlit environments and long-term exposure when a bike sits outdoors in the paddock or in transport. Polycarbonate, with its superior impact resistance and thermal stability, stands out for parts expected to see higher temperatures or more aggressive exposure to sunlight. These materials keep the parts from deforming under heat and maintain structural integrity when subjected to road dust, rain, and the vibrations of riding. It is important to note that standard PLA, a common beginner-friendly filament, is typically avoided for fairing applications. PLA’s low heat resistance and tendency to soften under the sun’s rays make it a poor choice for exterior automotive or motorcycle panels where temperatures and direct solar exposure can be a factor. The material science narrative here is not just about selecting a plastic that prints well; it is about choosing a material that maintains shape and performance in real-world riding conditions, often requiring a careful balance between stiffness and toughness. Beyond thermoplastics, the frontier of 3D printed fairings also includes the integration of advanced composites. The transparency between design and performance becomes truer when carbon fiber reinforcement is introduced as a post-process option or when carbon fiber filaments are embedded during printing. This reinforcement can dramatically improve impact resistance and dimensional stability, allowing thinner skin without compromising safety margins. Coatings and surface treatments further extend the life of the fairings by improving weather resistance, abrasion resistance, and colorfastness under long exposure to sunlight and road grime. Yet even as these materials and finishes push the envelope, the economic realities of manufacturing cannot be ignored. Additive manufacturing excels in rapid prototyping and low-volume production, where the value lies in the speed of iteration and the ability to test multiple geometries with minimal tooling costs. In mass production, however, the economics shift. The cost per part can stay higher than traditional molding methods, and the speed of production may not yet match the blistering pace of high-volume assembly lines. For this reason, 3D printed fairings have found their strongest footholds in high-end prototypes, limited-edition models, and competition settings where the performance benefits, customization, and fast feedback loops justify the investment. The architectural elegance of a 3D printed fairing lies in topology optimization—the art of redistributing material within a given boundary to achieve the highest stiffness with the least weight. Designers exploit lattice structures and graded densities to create zones that carry loads where they are needed most while shedding mass in noncritical regions. The result is a panel that behaves almost like a composite would, but with a single, integrated part whose manufacturing process can be tuned at the design stage. This kind of optimization would be far more challenging with traditional methods, where adding internal channels or lattices would require complex assembly sequences or multi-part components that introduce joints and tolerances that can compromise integrity. By contrast, a well-optimized lattice inside a fairing panel can provide stiffness where it matters for torsional stability while reducing inertia in the body that negotiates gusts and turbulence at speed. Aerodynamic performance benefits extend beyond mere weight savings. Designers can sculpt fairings to shape the boundary layer and manage flow separation. Internal channels can guide air to desired regions, cooling hot areas under direct sun or near engine components, and even dampen resonant vibrations that can otherwise translate into rider fatigue or perception of gnarly handling in certain riding regimes. The capacity to mold the internal geometry of a single part aligns with how race engineering has always pursued performance: reduce the number of interfaces, minimize points of failure, and maximize predictability under dynamic loads. Although the performance story is compelling, the safety and durability considerations remain central. In real-world scenarios, fairings must resist impact from debris, endure weather elements, and maintain structural coherence when subjected to rapid acceleration and deceleration. Post-processing steps play a crucial role in boosting durability, including surface sealing, chemical or mechanical smoothing, and external wraps or coatings that improve abrasion resistance and weather sealing. The choice to reinforce with embedded fibers or protective coatings is often a strategic one, balancing weight, stiffness, and durability with the rider’s specific application, whether it is a track-focused prototype or a custom street bike that honors a unique aesthetic. It is this balancing act—combining lightweight design, aerodynamic precision, and durable construction—that makes 3D printed fairings a compelling option in a domain where margins for error are slim and the cost of failure is high. Still, the narrative acknowledges limitations. While additive manufacturing enables rapid iteration and bespoke geometry, scale and repeatability in mass production remain as challenges. For teams deploying fairings in a professional racing context, the decision to adopt 3D printed panels often rests on a rigorous assessment of durability under track conditions, the ability to replicate critical mounting interfaces, and the overall lifecycle costs, including post-processing and maintenance. In practice, 3D printed fairings find their most meaningful impact where speed of iteration and customization deliver real performance and competitive advantages. Designers can test multiple curvature strategies to refine drag coefficients, experiment with cooling and airflow management, and tailor aesthetics without the heavy investment of tooling and molds. The broader implication for the motorcycle ecosystem is a shift in collaboration between design, engineering, and fabrication. Digital design tools enable a seamless handoff to additive manufacturing, while engineers can evaluate the effects of geometry on aerodynamics, weight, and heat management with fast feedback cycles. As a consequence, manufacturers, race teams, and individual builders can push the envelope of what is possible with skin and bodywork, selecting from an expanding toolkit of materials, structures, and surface finishes that collectively advance performance. The knowledge generated through this process is not isolated to the fairing itself. Lessons about boundary layer control, heat management, and structural distribution inform the broader engineering of the motorcycle platform, influencing how riders experience front-end stability, cornering confidence, and even the tactile feel of the machine at speed. For readers who want to explore this subject further, a detailed guide on material choices, performance standards, and practical considerations offers deeper insight into the trade-offs that accompany this technology. External resources provide a more technical dive into the design-to-test workflow, material properties, and real-world performance outcomes. The journey from concept to a finished, optimized fairing is a testament to how additive manufacturing reshapes traditional boundaries and enables a more iterative, data-driven approach to motorcycle performance and customization. For practitioners and enthusiasts, the chapter invites a careful balancing of engineering rigor with creative expression, reminding us that the skin of a speed machine is where science, craft, and daring play out in real time. External resource: https://www.matterhackers.com/articles/3d-printed-motorcycle-fairings-guide-what-to-look-for

null

null

Shape, Strength, and Speed: The Material Science Driving 3D Printed Motorcycle Fairings

Material science in 3D printed motorcycle fairings is a story of tradeoffs and breakthroughs. The fairing is not just a cosmetic shell; at speed, it becomes a critical component of the bike’s aerodynamic package, a shield against heat and debris, and a load path that helps define handling. The material choices determine what the design can achieve in terms of temperature tolerance, impact resilience, stiffness, and weight. With additive manufacturing, engineers can tailor a material to a specific performance envelope, then validate it through rapid prototyping and on-bike testing. The synergy between material science and topology optimization enables fairings that are not only lighter but also more aerodynamically efficient.

Prototyping material choices often begins with what is easy to print. PLA, the friend of the designer in the early stage, demonstrates geometry well and is inexpensive. Yet for anything intended to bear up under real-world riding at 200-plus kilometers per hour, PLA falls short. It softens under sustained heat from the engine bay and sun, and its impact resistance under dynamic loads is insufficient. Attempts to join PLA parts with methods like a 3D pen illustrate the gap between bench-top assembly and race-day reliability. Those experiments are valuable as learning tools, but they do not carry the performance demands demanded by professional or high-performance street riding.

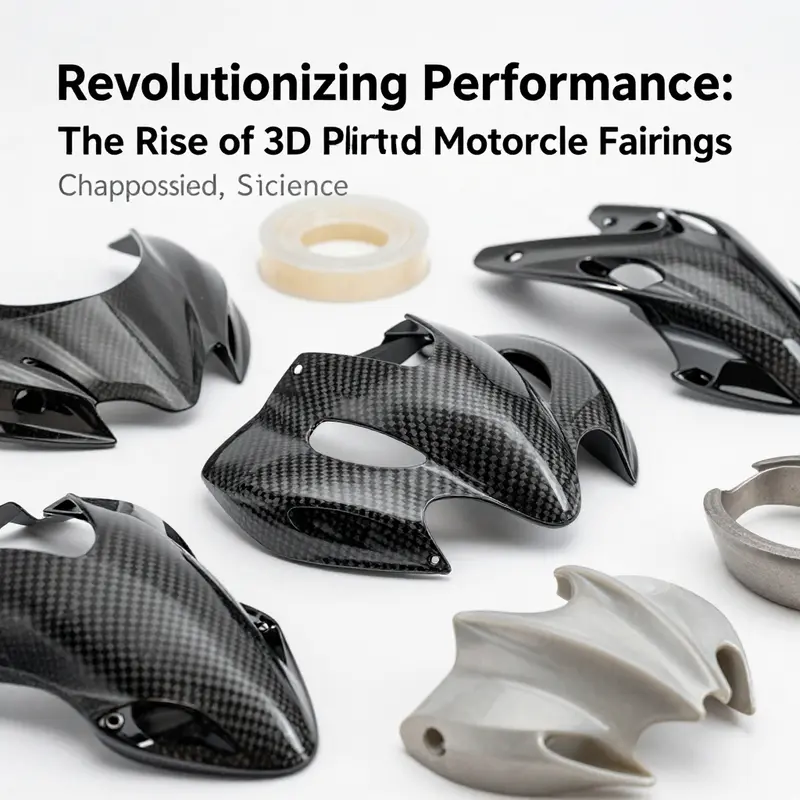

To meet those demands, the field has gravitated toward high-performance thermoplastics. ABS stands out for its toughness and thermal stability, while polycarbonate (PC) provides higher impact resistance and better heat deflection, which is crucial when the fairing skins sit close to hot exhaust routes and radiating surfaces. Composite-filled filaments—often carbon fiber or glass fiber reinforced states—bring stiffness and strength without excessive weight. The carbon fiber–filled variants can dramatically raise the Young’s modulus and reduce elongation, giving a more robust shell that resists deformation under gusty crosswinds and high-speed loads. Yet these materials come with processing challenges: higher nozzle temperatures, possible anisotropy due to print orientation, and the need for post-processing to achieve a smooth, paint-ready surface.

Beyond traditional plastics, metallic additive manufacturing expands the toolbox for the most demanding parts of the fairing structure. Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) or Electron Beam Melting (EBM) allow engineers to fabricate load-bearing elements with impressive strength-to-weight ratios. In practice, this means mounting brackets, spider structures that connect the fairing panels to the motorcycle frame, or reinforcements that must endure repetitive vibrational stress and air-pressure loads at high speed can be produced as single, integrated components rather than assembled from multiple parts. The results can be stiffer assemblies and improved crash performance due to more predictable load paths. These metal components also offer superior corrosion resistance and thermal endurance, qualities that matter in endurance events and long-term durability.

Material selection is never abstract. It is a balancing act that weighs printability, mechanical performance, thermal response, and weight. Engineering guides published in recent years emphasize that the right material is not only about what can be printed; it is about what can endure the dynamic forces, the aerodynamic loads, and the thermal environment of a real ride. Substandard materials pose safety risks, while the best-performing composites or metal alloys unlock the possibilities of lighter, more rigid fairings that still protect the rider. The choice also intersects with production realities. For small shops or boutique manufacturers, the economics of material cost, post-processing labor, and equipment depreciation shape what is viable. The opportunity lies in selective use: employ high-performance materials for critical surfaces and load-bearing features, while treating less stressed skin panels with more economical polymers that still meet surface finish and weather resistance requirements.

If we zoom in on the design workflow, material science informs every decision from geometry to finishing. Topology optimization can reduce mass while preserving stiffness in regions that experience the highest aerodynamic loads. Lattice structures or gradient infill patterns enable variable stiffness, where the leading edge can be stiffened to resist deformation, and the trailing edge can be optimized for energy absorption. Lightweight yet strong fairings benefit handling and fuel efficiency, especially when integrated with other air-management features such as near-skin radiative cooling paths and micro-channel cooling for electronics tucked into the bodywork. A well-planned lattice can also improve vibrational behavior, damping micro-motions that would otherwise amplify at high speeds. The resulting parts aren’t simply shells; they are engineered systems that contribute to the bike’s aero balance, downforce management, and even rider perception of wind noise.

In this sense, material selection extends into surface treatment and coatings. The unfinished surface of a 3D-printed panel can trap moisture, exhibit UV sensitivity, or show stress concentrations that could initiate cracking under load. Solutions include post-print sealing with weather protections, applying coatings that resist water pickup and UV degradation, and adding carbon fiber skin wraps that increase abrasion resistance while preserving the mechanical advantages of the core material. The coating strategy may also influence the perceived texture and finish, a factor that matters for branding and aesthetics in limited-edition builds. When done well, coatings can mitigate micro-cracking, reduce surface roughness that harms aerodynamics, and stabilize the color against sun fade, all without adding excessive weight.

A practical truth remains essential: not every fairing must be a single-piece metal-like shell. The fairing ecosystem benefits from a hybrid approach that leverages the best features of each material class. For example, a primary structural spider might be produced from lightweight metal alloys by additive methods, while exterior shells can be formed from carbon-reinforced polymers or high-temperature plastics that are easier to finish and paint. This strategy balances the need for strength and durability with the desire for surface quality and a broad color palette. Even with such hybridization, the role of material science is central—guiding how each piece behaves under heat, wind, and impact, how it couples to the frame, and how it interacts with the rider’s position.

Designers who want to push performance through materials often look to existing catalogs as reference points. Notably, established catalogs such as the Honda fairings collection offer practical examples of mounting geometry, attachment points, and fairing interfaces that have evolved through many generations of riding and racing experience. Access to these references helps teams understand tolerances, fitment challenges, and the realities of field maintenance. The choice of a material can be guided by known mounting patterns and serviceability expectations, which in turn influences wall thickness, hole sizes, and joint strategies. The synergy between reference catalogs and modern 3D printing creates a path from concept to functional, on-bike testing without an extensive tooling investment. Honda fairings collection demonstrates how existing shapes and interfaces inform material decisions that support durability while enabling design exploration.

The fragmentary nature of prototyping should not deter ambition. If 3D printed fairings are to become a credible option for production or racing, the material science must be accompanied by robust testing regimes. On-bike tests reveal how air-pressure loads, buffeting, and boundary-layer effects translate into panel deflection and noise. Environmental tests expose UV aging, humidity effects, and salt spray resistance that matter for street use. Thermal tests verify how well the panel skins manage heat from radiators, exhaust, and sun exposure. Tests can also reveal whether joint regions remain intact after repeated flexing, whether post-processed edges resist chipping, and whether coatings maintain their protective performance after stones and debris strikes. The test data feed back into both material choices and geometry, guiding iterative refinements that can shave seconds from lap times or improve street ride comfort.

In the current era, the path to reliable, high-performance 3D printed fairings also depends on the availability of advanced processing capabilities. Print direction, layer height, and orientation relative to anticipated loads all influence anisotropy—the tendency for printed parts to exhibit direction-dependent strength. The best-performing fairings exploit favorable build orientations and strategically placed reinforcements to counteract weaknesses introduced by layer-by-layer fabrication. Print speed, nozzle temperature, and cooling rates affect surface finish and dimensional accuracy, which matter for tight tolerances around mounting points and edge radii. Post-processing steps—even simple sanding and smoothing—can dramatically improve drag coefficients by producing smoother surfaces that minimize boundary-layer separation. The cumulative effect is a system that marries form and function, not just a single panel but a correlated network of parts that weather real-world conditions.

As the dialogue between design and material science continues, the end result is not simply a better-looking panel but a better-performing vehicle. Lighter, stiffer fairings reduce inertial mass and improve acceleration response, while more resilient skins allow for extended service intervals and fewer field repairs. The rider experiences gains that go beyond raw numbers: improved steering feel, reduced buffeting, and more consistent engine cooling. In racing, even minor gains can be decisive, with teams counting grams and seconds in equal measure. The material choices thus become part of a larger performance language, speaking to reliability, repeatability, and the courage to try unconventional solutions.

The material science trilogy—plastics, composites, and metals—forms a hierarchy that lets designers decide, for each panel and each attachment, whether to emphasize weight, stiffness, or heat resilience. The promise of 3D printing is not simply that parts can be made quickly; it is that the design space expands so much that engineers can relocate mass to optimize the entire bike’s aero profile. The result is a fairing system that behaves as a single, coherent aerodynamic body, not a loose assembly of panels. That coherence matters when riders push beyond speculative limits and when teams chase lap times that previously seemed unattainable. The integration of material science into the design cycle—through careful material selection, controlled processing, and rigorous testing—transforms additive manufacturing from a quick-turn tool into a strategic enabler of performance.

External resource for further reading: https://www.engineering.com/3d-printing/motorcycle-fairings-guide

Riding the Edge of Innovation: Market Trends and the Road Ahead for 3D-Printed Motorcycle Fairings

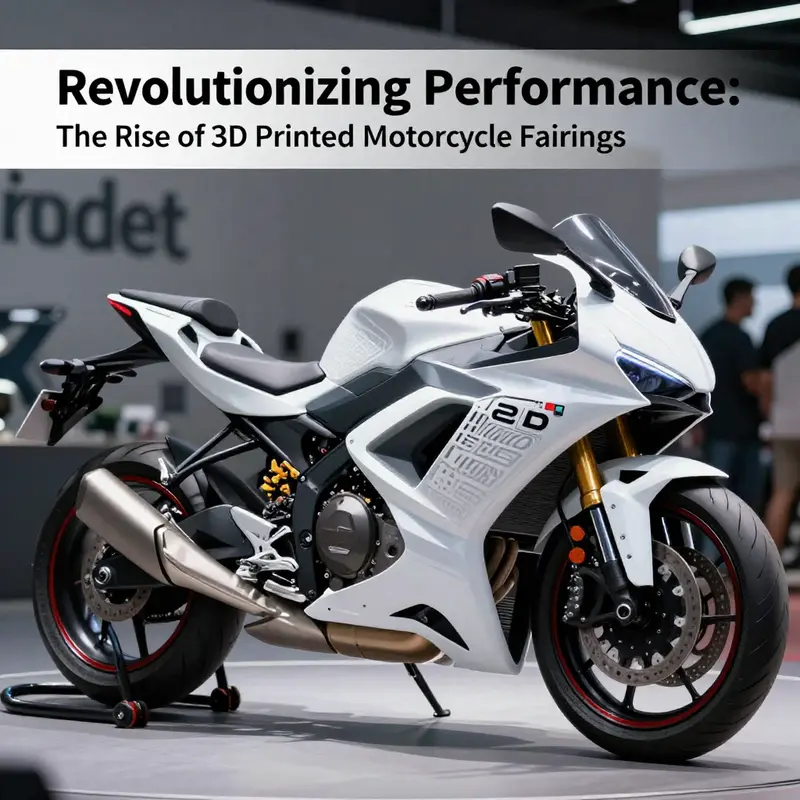

The market for 3D-printed motorcycle fairings is arriving at a moment when the gap between digital design and physical performance is narrowing. Across racing teams, boutique builders, and ambitious OEM programs, the appeal of rapid prototyping, on demand production, and custom aerodynamics is increasingly evident. The latest industry analyses project the global 3D-Printed Motorcycle Market to grow at a CAGR of about 13 percent from 2026 to 2033, signaling that additive manufacturing has moved from novelty to necessity for high-performance two-wheelers. This momentum is not merely about more parts made faster; it is about how design freedom translates into measurable gains on the track and in everyday riding. The ability to iterate quickly, test variants in real-world conditions, and validate wind tunnel concepts with actual prints changes how teams approach every square inch of a fairing. In short, 3D-printed fairings are evolving from proof-of-concept curiosities into integral components of performance, aesthetics, and identity in modern motorcycling.

What drives this shift is not only technology but a broader change in expectations. Riders and builders no longer accept off-the-shelf shapes that solve one problem while creating another. They want aero that adapts to climate, weight that respects handling, and surfaces that can be personalized without sacrificing strength or reliability. Additive manufacturing makes this possible at a scale traditional tooling cannot justify. Instead of paying for long molds and tooling, teams can produce multiple iterations in days rather than months. This speed is especially valuable in racing environments where marginal gains compound quickly. A single nuanced change to a fairing’s profile or vent placement can reduce drag, alter pressure distribution, and influence cooling, and when those micro-adjustments accumulate across the whole bodywork system, the payoff shows up in lap times, fuel efficiency, and rider feedback.

Material choices have become a core element of this agility. Heat-resistant thermoplastics such as ABS, ASA, and polycarbonate offer a practical balance of toughness, temperature tolerance, and dimensional stability under sun, rain, and road spray. These materials perform better in harsh environmental conditions than older plastics used in early experiments. Beyond weather resistance, their mechanical properties support structural integrity in impact scenarios and during vibration-rich highway rides. Designers also explore reinforced filaments with carbon fiber or other fillers to boost stiffness-to-weight ratios, enabling fairings that resist deformation while keeping mass low. In practice, this translates to more predictable handling, maintained aerodynamics at speed, and the possibility of thinner, more complex skins without sacrificing safety margins.

The way fairings are manufactured is evolving in parallel with materials science. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) and stereolithography (SLA) remain the workhorses, each with niche advantages. FDM excels for large, structurally resilient panels produced quickly and at moderate cost. SLA offers higher resolution surfaces and excellent dimensional accuracy, ideal when surface integrity matters for performance testing and wind-driven effects. In both cases, post-processing steps such as sanding, sealing, painting, and coatings play a critical role in achieving final performance and durability. The interplay between process and post-processing determines appearance and the smoothness of airflow, as well as resistance to weathering. For fairings meant to endure long seasons, a combination of surface coatings and careful post-processing can extend service life and preserve the integrity of lattice structures that enable weight savings.

A key design philosophy guiding modern 3D-printed fairings is topology optimization. Engineers use lattice structures and tuned internal voids to remove material where it does not contribute to strength while preserving or enhancing rigidity where it matters most. This approach lowers weight without compromising stiffness, important for controlling high-frequency vibrations and maintaining predictable aerodynamics at various speeds. Topology optimization also supports thermal management by shaping internal channels and external vents to maximize airflow and cooling, helping to mitigate heat buildup in critical components and the rider’s cockpit. The result is a fairing that reduces weight while directing airflow where it matters most for engine cooling and electrical reliability.

Industry indicators suggest the broader motorcycle fairing market remains robust, with a forecast CAGR around 12 to 13 percent from 2026 to 2033. The convergence of 3D printing with the wider market creates two complementary forces: demand for customization and demand for performance. Customization has become a core driver of consumer choice, with riders seeking one-off aesthetics, unique color schemes, and aerodynamic shapes matched to riding style and posture. The 3D-printed approach makes it economically viable to offer bespoke surfaces, trim details, and vent configurations that would be costly with traditional tooling. At the same time, material durability and UV resistance remain essential for long-term reliability, and sustainability considerations are increasingly part of the conversation. When a fairing lasts longer and maintains its properties, the environmental footprint of each build is reduced, aligning with broader industry goals.

In this evolving ecosystem, the aftermarket bodywork sector benefits from 3D printing by enabling rapid prototyping of novel forms and optimized aerodynamics without expensive molds. Testing multiple profiles in parallel, gathering rider feedback, and iterating toward an ideal solution accelerates the path from concept to ride-ready component. It also widens the palette of available shapes, blending performance-focused engineering with striking visuals. The cultural pull toward personalization in motorcycling makes additive manufacturing a natural fit for consumers who want both form and function.

Looking ahead, the future of 3D-printed motorcycle fairings is likely to be defined by closer alignment between design, testing, and production. Integrated design studios may use virtual wind tunnels alongside rapid prototype testing to shape final geometries before any printed part leaves the CAD file. The convergence of workflows with expanding material libraries and more sophisticated post-processing ecosystems will streamline development, while fairings evolve into precise aerodynamic tools with integrated cooling channels and tailored heat management. The line between form and function will blur further as riders experience better control, more efficient airflow, and a personal form language that remains durable under the elements. The market’s expansion is about expanding what is possible within the constraints of speed, customization, and safety.

For readers exploring practical choices, a catalog of fairing collections illustrates how a variety of shapes and finishes can be realized through additive manufacturing. The ongoing convergence of material science, printing technology, and racing-driven requirements means today’s print farms could become tomorrow’s standard suppliers for high-performance bodywork. The journey from concept to circuit is accelerated by digital tooling and disciplined use of lattices, coatings, and reinforcements that preserve performance in harsh environments. It is a journey that honors customization while acknowledging durability and safety.

Final thoughts

In summary, the integration of 3D printed motorcycle fairings signals a significant shift in how the motorcycle industry approaches design, performance, and market adaptability. By leveraging advanced manufacturing technologies, businesses can not only enhance their product offerings but also meet the unique demands of performance-focused consumers. As more companies embrace these innovations, the competitive landscape will continue to evolve, offering new growth opportunities for those ready to adapt and innovate in this dynamic market.