As the motorcycle industry evolved, 1965 marked a pivotal point with the introduction of the BMW R60/2, a model that combined engineering prowess with luxurious touring capabilities. With its innovative full fairing, it not only enhanced aerodynamics but also set the stage for the modern touring motorcycle. This article delves into the technical innovations that defined the R60/2, its historical significance as a landmark in BMW’s motorcycle legacy, and its cultural impact that resonates with biking enthusiasts even today. Each chapter unpacks a different facet of this iconic machine, showcasing why it remains a revered piece of motorcycle history.

Toward Comfortable Speed: The 1965 BMW with Dustbin Fairing and the Birth of the Modern Touring Twin

The road in the mid-1960s was opening up to longer journeys and higher speeds for riders who valued comfort as much as performance. Against that backdrop, a new motorcycle from a storied maker quietly redefined what touring could be. It did not shout about its capability; it demonstrated it through a carefully composed marriage of aerodynamics, engine design, and chassis engineering. What began as a pragmatic response to wind push and fatigue would later be remembered as a turning point for the concept of the modern touring motorcycle. The machine in question belongs to a family of machines that carried the reputation of a company built on reliability, but the specific model introduced a feature that would reframe expectations across the industry: a full fairing, engineered not for show but for function, that streamlined how riders could cover great distances with less wind fatigue and more stability at speed. In the context of the era, this was revolutionary. Most production bikes of the period carried open or minimal bodywork, leaving riders to contend with the buffeting and perilous gusts that could shake even the strongest wrists and spines. The new fairing did not merely wrap around the engine or the tank; it enclosed a portion of the rider’s experience. It created a more cohesive silhouette that served both the rider and the machine. This was not a cosmetic flourish. The design intent was to extend comfort, to enable longer moments of sustained speed, and to do so with a level of consistency that riders could trust on unfamiliar highway systems, long stretches of rural road, and the occasional peaky descent where the air pressure could become a test of nerves as well as metal. In that sense, the fairing was a practical answer to a persistent problem: how to maintain control and composure when the wind becomes a visible presence at the rider’s chest and helmet. The solution drew on a deeper philosophy that had already defined the brand in earlier decades—the belief that true efficiency is born from harmony among every system in the motorcycle, from the engine’s heartbeat to the rider’s posture, and from the drivetrain’s quiet, predictable motion to the aerodynamics that kissed the machine’s lines. To understand the significance of the 1965 machine, one must start with its core: the engine. The horizontally opposed twin, a classic boxer’s layout, offered a remarkable balance and natural vibration damping because opposing pistons cancel much of the shake that might otherwise travel straight through the chassis. This inherent balance translated into a smoother ride at speed, an essential quality when the rider is facing extended hours in the saddle. The engine worked in concert with the shaft drive, a hallmark of the marque that emphasized reliability and low maintenance on long trips. Shaft drive removed many of the delicate adjustments required by chain systems, reducing the ongoing attention a touring rider would need to devote to tension, lubrication, and alignment. The combination of a stable power delivery and a drivetrain that refused to fuss about maintenance meant that distance and weather became less a challenge and more a measure of the rider’s focus and stamina. Yet power and transmission alone do not shape a tourer’s comfort. The chassis and suspension—the way the machine translates road irregularities into something the rider can interpret without fatigue—are equally decisive. In the 1960s, suspensions were evolving rapidly, but this machine took a thoughtful approach. The front used telescopic forks, a relatively modern arrangement at the time, capable of absorbing small and mid-sized undulations with a degree of predictability the rider could trust. The rear swing arm, paired with hydraulic dampers, balanced passport-like ride quality with enough control for spirited corner work when the mood and the road allowed. The result was a motorcycle that could maintain stable, planted confidence at higher speeds, even when the road surface betrayed its smoothness. The full fairing’s role in this equation was to smooth the air that the machine encountered rather than to splinter it into a distraction. The shape—often described as a dustbin by enthusiasts for its rounded, bulbous volume—was not a mere stylistic choice. It introduced a more favorable interaction with the wind, directing air away from the rider and engine bay while reducing the drag that would otherwise sap speed and exhaust power. The fairing did more than weather protection; it contributed directly to the machine’s dynamic behavior. By shaping the airflow around the rider’s torso and the upper portion of the bike, it lessened the buffeting that can make higher-speed cruising an exhausting endeavor. In practical terms, this meant fewer wrist and shoulder strains, a more comfortable seated position, and the possibility of longer distances before fatigue set in. Yet the fairing’s benefits went beyond comfort. The improved drag characteristics also supported stability, reducing the tendency for the bike to wander when gusts appeared or when the rider shifted weight in the saddle. A straight highway line felt calmer, and the rider could sustain modestly higher speeds with more predictable handling. This synergy between fairing, engine, and chassis was no accident. Each component was designed with the others in mind, a holistic approach that mirrored BMW’s engineering ethos: you solve a problem by addressing every influence that contributes to the riding experience. The result was a motorcycle that could reshuffle the perceived boundaries of long-distance riding. Rather than delivering an engine with enough torque to escalate into a throttle-bearing sprint, the machine offered a measured, confident performance envelope. The rider could decide where to push the pace, knowing that the combination of aerodynamics and drivetrain would respond in a way that rewarded smooth inputs and disciplined technique. The 1965 machine also offered practical improvements that reflected a balance of tradition and innovation. The full fairing did not demand the sort of weight concessions that would undermine the machine’s nimbleness. Instead, it was integrated into the bike’s lines with a careful consideration for weight distribution and structural integrity. The aim was to keep the center of gravity in a favorable range, preserving steering feel and low-speed balance. In practice, that meant the fairing was mounted in a way that did not dramatically shift the bike’s mass center, even as it added a little forward weight. This careful packaging contributed to predictable handling at both slow maneuvering and high-speed cornering, a trait essential for riders who needed to feel confident on unfamiliar roads or during long, one-day rides where roads could surprise with grade changes, wind shifts, or debris. The fairing’s presence also interacted with rider ergonomics in subtle, meaningful ways. The rider’s posture could be kept more upright and comfortable, reducing the strain on the neck and shoulders that accompanies longer stretches of highway. Visibility remained a practical concern, of course, but the design sought to thread the line between protection and openness. The resulting cockpit felt more like a well-engineered shelter than a barrier, shielding the rider from wind pressure while preserving a sense of connection to the road. The machine’s instrumentation, often housed in an uncluttered dash, remained accessible and legible, reinforcing the sense that the rider and machine could operate as a single unit, not a rider struggling against a machine. In this sense, the 1965 BMW with fairing was not merely a technical novelty. It crystallized a philosophy about how long-distance motorcycling could be approached as an integrated system where aerodynamics, structural design, and mechanical reliability were designed to work in service of a single goal: making the ride feel effortless at speed and sustainable over many miles. The broader influence of this approach extended beyond the model itself. It influenced how riders thought about touring and how manufacturers imagined the capabilities of production bikes. The fairing’s legacy would echo through future designs, where wind protection and rider comfort became standard considerations in the pursuit of longer, more comfortable riding experiences, rather than optional add-ons for the dedicated few. The machine’s engineering narrative — the boxer twin’s smooth torque, the shaft drive’s reliability, the telescopic front forks and hydraulic rear dampers, and the fairing’s aerodynamic restraint — formed a template for touring bikes that would unfold over the next decades. Even as the motorcycle world around it experimented with more radical or more lightweight configurations, the 1965 model’s emphasis on balance and durability persisted as a core principle. It told a story about why riders travel: not to see how fast one could go for a few minutes, but how far one could go with confidence, comfort, and a sense of calm in the saddle. The dustbin fairing became more than a protective shell; it was a statement about the kind of relationship a rider could have with the road. It suggested that performance could coexist with endurance and that a machine could be tuned to reduce the toll of time spent in motion. In that sense, the 1965 BMW motorcycle with fairing did more than introduce a design feature. It endorsed a philosophy wherein engineering is a tool to enhance the rider’s experience, turning what might be fatigue into a manageable, even enjoyable, element of the journey. The result was a machine that, while rooted in its era, spoke to the future of motorcycling: a future in which touring remains a core passion, and where every mile traveled carries the promise of better balance between man, machine, and the wind. For readers curious about the historical specifics and technical context of the R60/5 and its place in BMW’s historical archive, the official BMW Motorrad resources offer detailed documentation and period imagery that illuminate how these machines were conceived and catalogued within the broader story of the brand. External resource: BMW Motorrad Historical Models – R60/5

Winds, Wheels, and a Turning Point: The 1965 BMW R60/2 and the Rise of the Modern Touring Fairing

Winds, Wheels, and a Turning Point

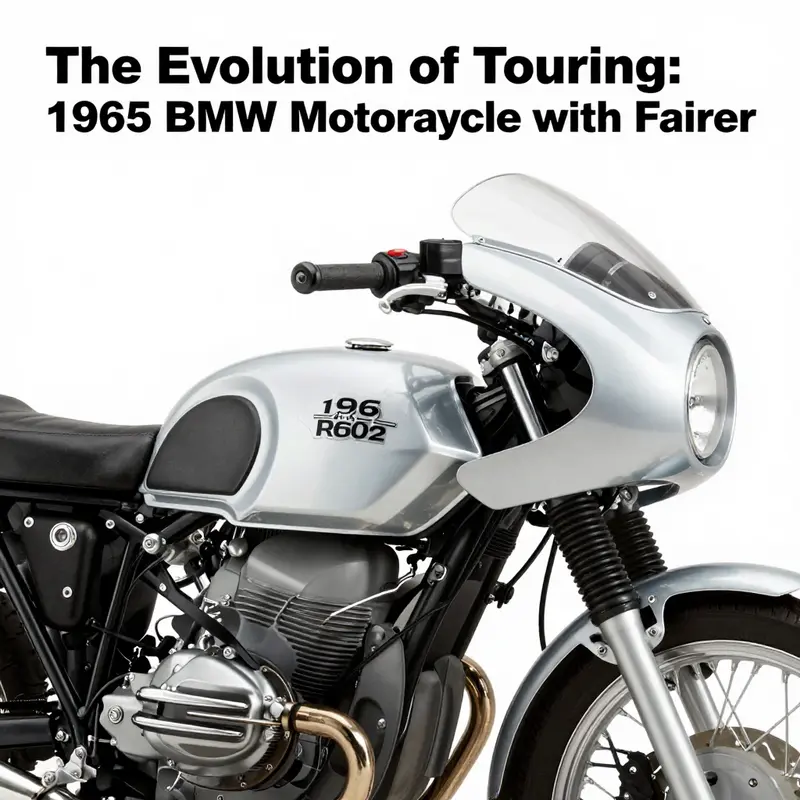

In the lineage of motorcycle design, certain machines mark a shift in purpose more decisively than others. The 1965 BMW motorcycle with a fairing—the BMW R60/2—occupies that kind of place. It is not merely a mid‑sixties rider’s tool but a symbol of a new conviction: long-distance riding would be about comfort, protection from the elements, and sustained endurance as much as about speed or nimble handling. The R60/2, powered by a compact and reliably balanced 599cc flat‑twin, sits at the crossroads where aerodynamics mute fatigue and design responds to the demands of the road, the weather, and the miles ahead. Its full fairing is not a garnish; it is a functional statement that shaped how riders perceived travel on two wheels, and it nudged the industry toward touring bikes that could carry a rider farther in more comfort and with greater consistency than ever before.

To understand the significance of this model, it helps to picture the riding environment of the time. The postwar motorcycle world was still largely a practical, air-cooled, minimalist affair. Riders would become weathered travelers on open strands of asphalt, their journeys punctuated by wind pressure, rain, and the mental load of keeping the machine on an ever‑more demanding course. There is a quiet elegance in the way the R60/2 integrates its fairing into that milieu. The full fairing, a notable feature for production motorcycles of its era, does more than shield the rider from wind. It compresses the open air around the bike into a more predictable flow, reducing buffeting at speed and smoothing the machine’s profile in a way that lowers fatigue during long hours in the saddle. The result is not only a more comfortable ride but a machine that invites longer, more deliberate journeys, turning the motorcycle into a viable alternative to a car for certain kinds of travel.

Beneath the fairing, the R60/2’s engineering tells a parallel story. The flat‑twin engine—two cylinders lying horizontally opposite one another—offers a low center of gravity, a high level of torque at modest speeds, and a character that rewards steady, methodical riding rather than explosive bursts. This was a package designed for the road as much as for the thrill of curve and climb. The fairing’s influence is visible in the way the machine presents itself: a balanced silhouette, a front that carries the eye forward with a hint of enclosure, and an instrument cluster that remains legible while seated behind a windscreen that deflects more air than it disturbs.

The decision to fit a full fairing to a production motorcycle was not merely a stylistic flourish. It represented a shift in BMW’s design philosophy and, more broadly, in the motorcycle industry’s approach to touring. Before this period, many touring riders leaned toward larger displacement bikes with little or no fairing, prioritizing mechanical simplicity and the flexibility of a naked, unadorned chassis. The R60/2 challenged that assumption. The fairing introduced a new equation: rider comfort and weather protection would become essential measurable outputs of a touring machine, not luxuries or afterthoughts. In this sense, the 1965 BMW with fairing stands as an early example of a design strategy that would, in the decades to come, become a baseline expectation for premium touring motorcycles from multiple manufacturers.

The fairing’s impact extended beyond comfort. Aerodynamics, a discipline often discussed in the language of race machines, entered the everyday lexicon of touring bikes. The enclosure and streamlined form reduce wind pressure on the rider, which translates into steadier steering at speed and less turbulence. This is not merely a matter of keeping the rider dry or warm; it is about sustaining a level of confidence when the road stretches into long, straight miles or into complex, gusty crosswinds. When a rider sits behind a fairing that has been thoughtfully integrated with the bike’s geometry, the sense of intention behind every line becomes clear. The design is not an ornament but a collaborator—an ally that shares the burden of distance so that the rider can focus on the road, the weather, and the plan for the journey ahead.

The cultural resonance of this model is worth noting. In the 1960s, motorcycle travel was increasingly imagined as a form of adventure that could be both practical and enjoyable. The R60/2’s fairing invited a broader audience to consider long trips as a plausible, even comfortable, pastime. It encouraged new expectations: protection from wind at highway speeds, reduced fatigue after hours in the saddle, and a sense that performance could be reimagined through comfort rather than through raw horsepower alone. Even among riders who preferred lighter, more agile machines, the R60/2 demonstrated that there was a real space for gear like a full fairing—space that would later be filled by a proliferation of touring models from BMW and from other makers.

In this context, the fairing’s introduction also signaled a shift in design philosophy. It suggested that form and function could converge in a single package—an aesthetic that did not sacrifice the rider’s comfort for the sake of a cleaner silhouette, nor did it privilege weather protection over the bike’s handling and balance. The R60/2’s fairing offered a coherent balance: the profile remained elegant, the lines did not appear clumsy, and the fairing’s integration did not overwhelm the engine’s character or the bike’s chassis. This coherence mattered. It made the concept of a touring motorcycle more legible to the public and more defensible within engineering conversations. A touring bike needed to be credible in the long run, capable of crossing landscapes, and the R60/2 suggested that not only could this be done with grace, but that it could be done with an instrumented, purposeful design language that manufacturers could study and emulate.

The broader industry’s response to BMW’s step with the R60/2 was not uniform or instantaneous; change rarely is. Yet the ripple effect was real. Dealers and riders began to associate fairings with comfort and reliability in long-distance riding. Other manufacturers, observing BMW’s success with a factory‑level solution, tested their own ideas about airflow, protection, and cabin-like comfort—often borrowing or refining the basic approach of a front fairing framed by the machine’s anatomy rather than tacked on as an afterthought. The R60/2’s full fairing helped to normalize the idea that a motorcycle could be purpose-built for the traveler who logs miles year after year, not just the rider who enjoys weekend spins. Over time, this mindset would mature into a more diverse touring category, a class in which a rider could select machines with varying degrees of fairing complexity while maintaining the core promise of comfort on the move.

The technical story behind the R60/2’s fairing complements this narrative. The fairing interacts with other design elements, like the protective coverage over the handlebars and the cockpit’s ergonomics, to create a more inclusive riding stance. The rider is shielded not only from the elements but from wind pressure that would otherwise drain energy and focus. This translates into more consistent control, particularly at higher cruising speeds and on gusty roads. The mechanical balance of the bike—its weight distribution, the low‑rigidity, air‑cooled engine, and reliable suspension—works in concert with the fairing to deliver a ride that feels steadier and more predictable. The result is a machine that invites travel rather than merely enabling it. In that sense, the R60/2 embodies a philosophy that would underpin BMW’s own future touring efforts and influence the broader market’s expectations about how motorcycles should carry a rider across continents without forcing a compromise between performance and comfort.

From a rider’s perspective, the 1965 R60/2 with a fairing offers a vivid case study in how a single design decision—where to place the windshield, how to shape the front fairing, and how to integrate it with the bike’s silhouette—can change the calculus of riding. The fairing reduces fatigue by damping wind noise and by smoothing the pressure against the rider’s torso. It also provides practical benefits for weather protection, helping a rider stay drier in rain and warmer when temperatures drop. The net effect is more miles achieved in a day and, crucially, more days in the saddle without the kind of soreness that would deter long trips. The rider’s experience becomes less a test of endurance and more a procedure of consistent, controlled motion. In this way, the R60/2’s fairing helps recast touring as a discipline that rewards planning and care—attributes that were becoming increasingly valued as more riders sought to explore distant horizons on two wheels.

The significance of the R60/2 with its fairing also extends to the lasting cultural image of BMW as a brand that marries engineering integrity with an unfussy, user‑centric sensibility. The bike’s design does not rely on flash or flamboyance. Instead, it communicates confidence, predictability, and a certain quiet sophistication. That attitude resonates with a rider who values the journey as much as the destination and who recognizes that a machine’s worth is measured not only by its top speed or its sprinting ability but by how well it supports a road, a season, and a lifetime of travel. In this light, the R60/2’s fairing is less a novelty and more a foundational element in a broader narrative about how motorcycles evolved to accommodate the traveler within. It foresees a future where touring, long-distance reliability, and rider comfort become central to the design brief—an arc that has continued to unfold through the decades, with each new generation building on the lessons learned from those early, bold experiments in enclosure and aerodynamics.

To appreciate the lineage of this idea, one can trace the thread from the R60/2 to later touring machines and to the way manufacturers articulate comfort as part of core performance. The fairing, once a novelty on the edge of innovation, becomes almost a given on many long-range motorcycles. The point of departure remains clear: protect the rider, stabilize the ride, and allow the machine to reveal its character over the miles rather than at the end of a straightaway. The R60/2’s bold step, therefore, is not merely a historical footnote; it is a reminder that the evolution of the touring motorcycle is as much about thoughtful human factors as it is about technical prowess. The machine invites riders to plan their itineraries with a sense of inevitability about the journey, a testament to how design can alter expectation just as much as performance.

In the broader chronicle of motorcycle history, the 1965 BMW R60/2 with a full fairing marks a critical moment when the line between sports machine and travel companion began to blur in a productive way. It offered a tangible proof of concept: that a well‑designed fairing can harmonize with an engine’s torque and a chassis’s balance to deliver miles of comfortable, dependable travel. It is a model that deserves remembrance not only for what it did in its own right but for the way it opened doors—doors to new questions about rider protection, aerodynamic efficiency, and the poetic possibility of touring as a central, sustainable mode of motorcycling. As the decades passed, the idea persisted and grew, matured by new materials, new testing methods, and a broader culture of adventure and exploration on two wheels. The R60/2 remains a touchstone in that ongoing conversation, a reminder that sometimes the most enduring innovations arrive not with a roar of horsepower but with a steady, patient reimagining of how a bike can carry a rider across a landscape that is as challenging as it is inspiring.

For readers curious about the historical arc and broader context of this landmark, additional background can be found in resources that trace the evolution of BMW’s touring philosophy and the development of fairings across the industry. In particular, the official BMW Motorrad history page provides a concise overview of the model’s place in the company’s story and its role in shaping how touring motorcycles were imagined and engineered. BMW Motorrad History.

As a final reflection, the 1965 BMW R60/2 with its full fairing invites us to consider what it means for a machine to carry a rider not just over terrain but through time. It embodies a shift from a focus on raw mechanical prowess to a more inclusive understanding of riding that foregrounds comfort, protection, and the reliability needed to embark on journeys that extend beyond a single day’s ride. The fairing thus stands as a forward‑looking solution in an era when the road was rapidly expanding, and the idea of what a motorcycle could be—what it could do for a traveler—was expanding in tandem. The chapter of this machine in the history of motorcycling is not merely about gear and design; it is about aspiration—the aspiration to ride farther, with fewer interruptions, and with a sense that the machine and the rider move together toward a horizon that feels both reachable and inviting. In that sense, the R60/2 with its fairing did more than improve aerodynamics or reduce fatigue; it redefined what a touring motorcycle could promise to the riders who believed that a journey is as much about the experience of arrival as the thrill of departure.

For those who want to explore how fairings have evolved in other brands as part of the ongoing conversation about rider comfort and aerodynamics, you can browse a broader selection of offerings that illustrate the variety of approaches across marques. For instance, the Honda fairings collection showcases a range of styles and integration philosophies, illustrating how different design languages translate the same goals of protection and performance. Honda fairings collection.

External resource: For a detailed, primary source account of the R60/2’s development and its place in BMW’s touring narrative, visit the official BMW Motorrad History page referenced above.

Dustbin Icon: The 1960s Bavarian Touring Bike and the Dawn of Modern Motorcycling Culture

In the middle of the last century, motorcycle design began to teach riders a new vocabulary of comfort, capability, and purpose. A single machine from the Bavarian maker shifted that vocabulary forever. It arrived not as a flamboyant sprint bike but as a practical, purpose-built tourer whose most striking feature was a large, protective shell wrapped around the front end. The fairing, bulky yet undeniable in its presence, became a symbol of an idea: that a motorcycle could be more than a machine for speed or simple transport. It could be a companion for distance, a vehicle that carried a rider across landscapes with a sense of ease and restraint. The story of this machine is less about a single corridor of performance and more about a cultural moment when form and function began to speak the same language in public, print, and on the road. It is a story about how a design decision, born from a desire to improve long-haul comfort, rippled through motorcycle culture and helped seed the modern touring ethos that endures in showrooms, garages, and custom builds to this day.

The design philosophy behind this touring-focused machine rested on a simple, almost obvious premise: wind is a force. For riders covering long distances, wind is not merely a nuisance but a source of fatigue, noise, and drag that can erode stamina and concentration. The fairing was conceived as a solution to this problem, a protective enclosure that redirected air around the rider and engine. This was more than aerodynamics for the sake of speed; it was about a more humane riding experience. The frame and bodywork worked in concert to offer calmer air pressure, reduced buffeting, and a more stable ride at highway speeds. In that sense, the machine anticipated a broader shift in motorcycle design—the move from naked, exposed machines toward integrated, all-weather travelers that could handle the long road and the occasional expedition with equal poise.

Behind the fairing, the mechanical heart of the machine was every bit as purposeful as its outward shell. The Bavarian maker emphasized a boxer engine—a horizontally opposed twin that kept the center of gravity low and the mass balanced. This configuration offered smooth torque delivery and a level of versatility suited to mixed road conditions and varying loads. The powertrain was tuned not for blistering top speeds but for predictable, usable power that could be harnessed reliably on long rides. This was the essence of touring engineering: a balance between performance, reliability, and endurance. The drivetrain, in harmony with the chassis, allowed a rider to maintain comfort over hours and miles, a feature that, at the time, separated the good touring bikes from the merely adequate ones.

The fairing itself deserves a chapter of its own in any conversation about mid-century motorcycle aesthetics. Its silhouette often earned the moniker of a dustbin—an exaggerated, almost industrial form that wrapped around the front and extended into generous wind protection. It was not about sleek linework alone; it was about a utilitarian honesty. The fairing signaled to onlookers that this bike cared about rider welfare as much as about poster-worthy speed. The visual language—blocky geometry meeting metal and glass—became a striking counterpoint to the more traditional cruiser profiles of the era. In the eye of observers, the machine looked forward, even as it was rooted in a postwar manufacturing ethos that prized precision engineering, durability, and a certain minimalist restraint. The result was not merely a machine with improved aerodynamics. It was a sculpture of function and calm, a machine that invited a rider to imagine long journeys as approachable realities rather than exceptions to daily life.

Culturally, the impact of this design extended beyond the technical. It became a marker of identity for a generation of riders who valued efficiency, practicality, and quiet elegance as a response to a complex world. The Baverian maker’s approach—calmly integrating the fairing into the bike’s overall silhouette and ensuring it did not overwhelm the machine’s character—spoke to a broader cultural preference for restraint and discipline in an era that often celebrated exuberance in other forms. The result was a bike that looked serene while delivering a sense of power that felt controllable, approachable, and trustworthy. This combination—rational engineering paired with a distinctive, almost sculptural form—made the bike instantly recognizable. The shape itself became a cultural symbol, a visual shorthand for a philosophy of travel that prized comfort, reliability, and the idea that riding could be both meaningful and enjoyable over long distances.

The fairing’s visual language did more than shape aesthetics; it offered a platform for a cultural dialogue about how motorcycles should relate to riders’ bodies and to the landscapes they traversed. The bulky front shell redirected wind and weather away from the rider, enabling a degree of weather resistance that previous designs struggled to provide. Riders could lean into miles of highway with less fatigue and more confidence. That practical shift helped redefine what people expected from a touring motorcycle. No longer was long-distance riding a test of endurance alone; it was a coordinated interaction between rider, machine, and environment. The fairing facilitated this dialogue, becoming a shared symbol of a kinder, more purposeful relationship with the road.

As the machine found its footing in the culture of riding, it also influenced design conversations within the broader motorcycle industry. It offered a proof of concept that aerodynamics could coexist with classic motorcycle lines and still produce a distinctive personality. The fairing did not erase the machine’s mechanical character; it highlighted it, turning the front end into a merging point where performance, protection, and design converged. The result was a new vocabulary for touring bikes—one where a rider could embark on a long journey without surrendering the machine’s aesthetic identity. The dustbin-like silhouette became not merely an engineering solution but a cultural artifact that other designers and builders encountered and reinterpreted in their own ways. Enthusiasts learned to appreciate how form could serve function so gracefully that the line between industrial design and art began to blur.

The influence of that era’s design language extended beyond the factory floor. Custom builders and riders began to reinterpret the dustbin fairing in countless ways, adapting it to different bodies, climates, and riding styles. The idea of a protective shell around the rider found adoption in various forms, from oversized fairings created to tackle long-distance touring in harsher weather to more compact, sport-touring configurations that still preserved the sense of a protective, forward-facing cocoon. The cultural footprint of the era can be traced not only in period magazines and showroom catalogs but in the countless conversations that followed in clubs, garages, and online forums. The sense that riding could be enhanced by thoughtful, purposeful design became a shared conviction that endured as new generations rediscovered vintage design through restoration projects, rebuilds, and modern reinterpretations.

In the late stages of the 20th century and into the modern era, the legacy of this design choice helped establish a broader perception of the manufacturer as a serious global player in the motorcycle market. It contributed to a reputation for precision, reliability, and a restraint in style that contrasted with flashier contemporary trends. The message was clear: a well-made touring motorcycle could be both an instrument for travel and a piece of technical craftsmanship that spoke to a rider’s taste and sense of responsibility. The cultural effect, then, goes beyond the bike’s physical form or its mechanical gains. It introduced a way of thinking about motorcycles as companions for exploration, partners that could be trusted to perform consistently over long horizons while still telling a story through their appearance. That story remains legible in today’s retrospectives, exhibitions, and online discussions, where the dustbin fairing continues to symbolize an era when engineering and aesthetics learned to walk in step.

In examining contemporary references to vintage touring design, one finds a rhythm of admiration and re-interpretation. Modern riders and builders frequently revisit those mid-century calculations about weight, balance, and aerodynamics, translating them into new forms that honor the past while acknowledging present technologies. It is not simply nostalgia; it is a careful study of how a well-designed feature can shape rider behavior, market expectations, and the way a machine is perceived. The dialogue between then and now is a quiet, sustained conversation about what it means for a motorcycle to be more than a means of transport. It becomes a partner for discovery, the way a well-considered fairing enables a rider to push farther, stay longer, and feel more connected to the road. The enduring appeal of this design can be seen in the way collectors, restorers, and curious newcomers approach vintage examples, recognizing that the value of the machine lies as much in its philosophy as in its mechanics.

To explore the broader ecosystem of fairings and how historical designs inform current practice, readers may consider modern iterations in related collections that continue to emphasize the balance between protection, aerodynamics, and aesthetic clarity. For instance, the Yamaha fairings collection offers a contemporary reference point for how fairings are designed to integrate with a bike’s silhouette while serving rider comfort and performance needs. This lineage—the throughline from the dustbin to today’s refined partitions—demonstrates how essential it is to view fairings as an evolving language rather than a one-off solution. The link below points to a resource that showcases how modern fairings are organized and presented across different models, underscoring how the principles of that era persist in today’s design conversations. Yamaha fairings collection

The cultural arc also reflects how motorcycles function within social contexts. The design and its narrative resonated with a postwar generation that sought efficiency, mobility, and a sense of independence anchored in advanced engineering. It is not an accident that the same era that produced this iconic touring shell also produced a growing interest in travel writing, road trips, and cross-country journeys. The machine, with its protective shell and refined balance, embodied a new kind of mobility—one that could carry a rider through unfamiliar landscapes with a quiet confidence. This is where design became culture. A fairing that looks purposeful and behaves predictably can invite a rider to dream bigger, to consider longer routes, and to rethink the relationship between rider and machine. It is a subtle invitation, one that helped redefine what it meant to be a motorcyclist during a pivotal decade and beyond.

The ongoing dialogue about vintage touring design also sheds light on how communities remember and celebrate historical machines. Collectors curate archives, restoration guides document period hardware with care, and exhibitions gather fans who want to experience the atmosphere of a mid-century road trip on wheels. In digital spaces, discussions revolve around how to preserve the balance between originality and usability, how to maintain mechanical reliability while honoring the machine’s design language, and how to keep the narrative alive for new audiences who encounter these bikes for the first time in online images or in person at a retro-themed event. The chapter of design history that began with a practical wind shield and a robust, weather-sealed ride continues to influence how people conceive of the touring motorcycle today. It reminds us that aesthetics and ergonomics can be inseparable from a rider’s wellbeing and a bike’s longevity.

As this exploration suggests, the 1960s Bavarian touring machine with its distinctive front shell did more than improve aerodynamics or rider comfort. It launched a culture, a vocabulary, and a set of expectations that echoed across decades. It helped grant touring a new legitimacy in the public imagination, turning long-distance travel from a functional activity into a philosophical proposition about how engineering can shape everyday life. That legacy persists in the way brands approach the design of modern sport-touring machines, in how restorers approach a dustbin-inspired fairing, and in the way riders talk about comfort, control, and character when they look back at a pivotal moment in motorcycle history. The fairing, once a practical feature, became a symbol, a reminder that the best machines are often defined by what they enable—confidence on the road, a sense of deliberate purpose, and a visual statement about the relationship between rider and machine.

For those who wish to glimpse the raw visuals that sparked this enduring conversation, a wealth of archival and contemporary imagery offers a path to understanding the fairing’s enduring appeal. The dustbin silhouette remains instantly recognizable to enthusiasts and casual observers alike, a reminder of an era when design decisions were as much about experience as about engineering. The fascination is not merely about how a bike looks; it is about how a bike makes a rider feel—protected, capable, and connected to a broader history of movement and exploration. In this sense, the 1960s touring machine with its bold front shell did more than advance a technical solution. It helped rewire the culture of motorcycling itself, encouraging riders to see a journey as a collaboration between human intention, mechanical reliability, and the landscapes that lie ahead.

External resource for visual context and historical references: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/123456789012345678/

Final thoughts

The 1965 BMW R60/2 stands as a testament to the blending of innovation, history, and cultural significance in motorcycle design. Its introduction of the full fairing not only enhanced performance but also paved the way for future touring motorcycles, influencing countless riders and manufacturers alike. Understanding its impact helps appreciate how this model has shaped the motorcycling experience we know today, continuing to inspire passions for riding and exploration. The R60/2 serves not only as a fine machine but as a cultural icon, encouraging a worldwide love for the open road.