The motorcycle market is an ever-evolving landscape characterized by a plethora of choices in parts and accessories. For owners of 2006 European motorcycles, unpainted fairings present a unique opportunity to blend performance enhancement with personalized aesthetics. Understanding the specifications of these fairings, their availability on the market, and the potential for customization is crucial for business owners looking to meet the demands of passionate motorcyclists. This article delves into these aspects, equipping you with the insights needed to better serve your clientele while driving your business growth.

Bare Panels, Bold Personalities: The Craft and Context of 2006 European Unpainted Fairings

Around 2006, European motorcycling culture carried a tension between factory perfection and the garage’s quiet rebellion. The unpainted fairing kit—an entire body panel package delivered in a blank, paint-ready state—captured that tension with unusual clarity. It offered the promise of a personal signature on a machine that, from the showroom, wore someone else’s design language. In the mid-2000s, the market for these blank canvases was not merely about aesthetics. It was a practical pathway to customize a bike that might have been bought secondhand, or sprung from a limited European model run, and to do so without gambling on the cost and wait of a full factory repaint. The unpainted fairing kit was more than a cosmetic option; it was a statement about the rider’s relationship to mass production and to the road.

The material story behind these kits is a recurring reminder that functionality and finish often begin in the same place: the injection mold. ABS plastic—chosen for its balance of rigidity and lightness, its ability to absorb impact without shattering, and its readiness for a paintable surface—emerges as the backbone of most aftermarket unpainted fairings. The choice of ABS is not incidental. In European service corridors where temperatures swing between chilly mornings and warm afternoons, ABS offers resilience without the brittleness that can accompany cheaper plastics. The best kits in the 2,000s, and the ones that still draw interest today, lean into this compatibility with heat resistance and a surface that can hold primer, color, and clear coat without warping or color shifting. Some manufacturers even fold in heat-shield or heat-dissipation technology to manage the tailpipes’ and radiators’ warmth that seems to migrate up along the fairing’s inner surfaces. The result is a clean, robust shell that can take the rigors of street riding, track days, and city commutes, all while preserving the factory lines that drew the original owners to these machines.

Fitment, in this context, matters almost as much as material. Unpainted fairing kits released for 2006-era European motorcycles are developed with a focus on precise geometry. These are not generic shells. They are engineered to line up with the mounting points, to align with the tank, to leave access for fasteners, and to accommodate the riders’ need to inspect, service, and adjust components beneath the skin. The approach to compatibility tends to be broad enough to cover several related models within a family—often spanning a year or two around 2006—yet still tight enough to deliver a factory-like fit. The goal is a seamless exterior that requires little modification. This is a significant practical advantage for the owner who operates on weekends and works on the bike in spare hours rather than in a professional workshop. The kits aim for a one-piece-in, one-piece-out installation philosophy: remove the old panels, align the new unpainted shells, tighten the fasteners, and you are back into the riding routine with minimal downtime. Given the European market’s diversity of brands and engineering philosophies in that era, this level of fitment precision was both a selling point and a challenge for manufacturers who specialized in mass-market aftermarket components. In effect, the unpainted fairing becomes a test bed for the intersection of global manufacturing standards and regional maintenance realities.

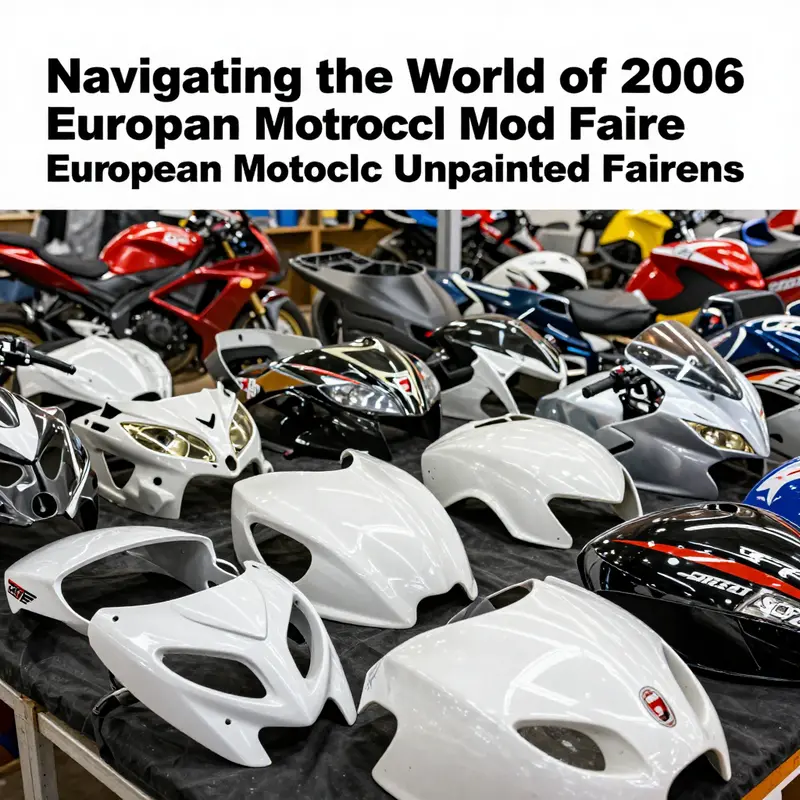

Quality, as listed by dealers and marketplaces, is typically framed in a compact, almost clinical way: 100% brand-new aftermarket, built to OEM-like specs, and presented as a full bodywork set that often includes the front fender as well. This framing matters because it reassures a rider that the investment is not a loose collection of panels but a coherent system designed to reconstitute the bike’s outer form and, by extension, its aerodynamics and protection. Yet the nakedness of the fairing—unpainted, unadorned, a blank slate—also invites a kind of risk assessment. The material may be robust, but a rider has to know the finishing journey ahead. The bare shell invites sanding, priming, and coating, each step a hinge point where costs, time, and skill meet. The promise is the opportunity to define a color scheme that resonates with personal taste, team colors chosen for a track day, or the nostalgic memory of a ride through a favorite European road. This is in part why the community around unpainted fairings flourished: it was a space where riders could experiment with aesthetics while maintaining the mechanical harmony of the machine. The fairing’s silhouette, its curves and cutaways, would persist, but the color and texture would carry the rider’s own signature. And in Europe, where regional pride often extends to the motorcycles that share the road, this personalization carried a unique social dimension. It was less about chasing a showroom look and more about cultivating a personal narrative around a machine that might have been acquired through a local dealer, a broker, or a used-bike market.

The philosophical shift that unpainted fairings embodied—the move from factory-defined color to custom artistry—also had practical underpinnings in costs and turnaround. The European consumer in 2006 faced a market where repainting a bike could be expensive and time-consuming, with the paintshop’s schedule dictating when the owner might be back on the road. An unpainted kit offered an alternative: a direct path to paint, in a controlled sequence, at a time chosen by the owner. This was not only a matter of saving money but of preserving the bike’s original engineering integrity during the repaint process. The unpainted panels allowed the owner to plan color schemes around a particular season, track schedule, or club event. In some garages, enthusiasts would lay down multiple color tests on spare panels, building a palette that would eventually find its way onto the fairing as a single, cohesive design. In others, the bare panels became the first step in a longer restoration or customization arc—particularly for bikes with a loyal following in European riding clubs, where a group’s color identity could be carried onto the fairing’s surface as a shared statement of belonging.

From a performance perspective, the unpainted state of the shell does not imply a reduction in aerodynamics. The fairing’s primary function remains shielding the rider from wind and debris, guiding airflow, and stabilizing the bike’s lateral dynamics at speed. In practice, the installed kit’s aerodynamic impact is driven primarily by the geometry of the panels, their three-dimensional shaping, and their interaction with the windscreen, seat unit, and rider posture. When owners choose to paint, the finish must preserve those critical relationships. A poor paint job or a heavy clear coat may introduce micro-changes in weight distribution or airflow tracking, though in most cases the differences are subtle and well within the margins of rider perception. This reinforces a broader truth about maintenance in European riding culture: the exterior finish matters, but the reliability of the underlying structure—mounting points, edge radii, fit to the frame—resonates more deeply with rider confidence than a gloss finish alone. The unpainted fairing, then, simultaneously invites artistic exploration and demands technical respect.

The aftermarket ecosystem that supported these kits was a pragmatic ecosystem, built on the needs of riders who wanted options beyond the limited color palettes offered by the factory. Third-party manufacturers produced complete bodywork sets that could be shipped as packages, including front fenders and the major side panels, sometimes even the tank panels or tail sections, depending on the kit’s scope. A seller would advertise the set as a near-OEM replacement, with tight tolerances and a finish that, prior to painting, could be prepared to accept primers and topcoats with minimal surface preparation. The language around these products—new, aftermarket, designed for a specific year range—shaped buyer expectations. In Europe, where regulations around vehicle maintenance and modification are relatively permissive and where a culture of DIY work remains robust, these kits could be purchased by experienced hands who would commit to a painting project during a winter layoff or a long autumn break. For a novice, the unpainted shell could be a more daunting project, but it still offered a structured way to approach customization rather than relying on a one-off spray job that might not account for the fairing’s curvature or the intricacies of edge finishing.

The social dimension of this practice is perhaps the most telling. In countless European garages, the unpainted fairing was a canvas for experimentation, a way to demonstrate skill and taste without tying the bike’s identity to a pre-made color story. It became part of the ritual of ownership: removing old panels, clearing mounting points, prepping for paint, laying down primer, applying masking for color separation, and sealing with a protective clear coat. The work could be a solo pursuit or a shared project among friends in a riding club, where the stories around the paint job—what colors were chosen, why certain lines were emphasized, how decals would be applied—b e c a m e a social currency. The unpainted fairing thus carried not only the promise of improved aesthetics but a narrative of hands-on craft, of a rider turning a machine into a personal artifact through the patient art of finishing.

In considering the broader history of unpainted fairings in 2006 Europe, it is helpful to place these kits within a continuum of aftermarket experimentation that spans decades. The practice echoes earlier eras when riders balanced the desire for factory-level appearance with the need to manage costs in a performance-focused environment. It also aligns with Europe’s enduring preference for customization as a form of self-expression—one that respects the mechanical backbone of the motorcycle while inviting a broad spectrum of stylistic possibilities. The 2006 window, in particular, marks a moment where the convergence of accessible ABS plastics, global supply chains, and a growing appetite for individualized aesthetics created a vibrant, if transient, marketplace. Today, the legacy of that moment is visible in the way modern fairings are designed to be easily painted, the rise of pre-finished shells that mimic factory colorways, and the continued appeal of a blank canvas—whether for a race team’s livery, a personal color story, or the simple pleasure of crafting something new from something old.

For the rider who seeks a blend of cost efficiency, mechanical integrity, and personal expression, unpainted fairings of the mid-2000s offered a measured middle path. They allowed a motorcycle to be rebuilt or refreshed without surrendering the chance to tell a story through color, line, and finish. They acknowledged that the European road, with its diverse climates and long winter seasons, often rewards a project that begins at the bench and ends on the road. They also remind us that, beyond the performance data, a motorcycle is a form of personal art—a machine that invites its owner to decide how it will present itself to the world. The blank shell is a symbol of that invitation: a canvas that keeps its own pace with the rider’s ambitions, waiting for the moment when paint meets panel and the machine becomes a living sculpture of speed, memory, and taste.

In closing, the story of the 2006 European unpainted fairing is not simply about a product category. It is about a moment when riders, fabricators, and suppliers recognized that a bike’s outer shell could be as much a creative platform as a protection layer. The fairing became a vehicle for dialogue—between rider and machine, between hand and tool, and between tradition and possibility. The unpainted panels offered a chance to honor the machine’s engineering while writing a new visual grammar, one layer of clear coat at a time. And when the next chapter of a bike’s life begins, it may well be because someone chose to strip away the familiar, lay down a fresh canvas, and let a new design language emerge from the honest, unpainted beauty of the shell.

Internal resource for readers seeking a practical entry point into related customization options can be found here: Suzuki fairings. This link points to a broader catalog where readers can explore available fairing sets and understand the kinds of components that typically arrive in unpainted form, though model-specific fit and compatibility must always be confirmed for any given year and chassis. An external reference that offers contemporary context for unpainted fairing kits and their market presence is available here: https://www.aliexpress.com/item/1005002494852483.html. The listing demonstrates how unpainted fairing bodies continue to circulate in today’s online marketplaces, underscoring the enduring appeal of a blank slate that riders can tailor to their own design language.”

From Primer to Palette: Unpainted Fairings and the 2006 European Motorcycle Aftermarket Landscape

In 2006, the European motorcycle scene was a study in balance between engineering precision and the urge for personal expression. Manufacturers offered bikes that balanced performance with durability, yet the visual language of a machine—its lines, its stance, the way a rider can claim ownership with color and texture—remained a vital part of the riding experience. For many European riders, the path from factory paint to a personal statement ran through the unpainted fairing kit. These kits, sold in an unpainted state, provided a practical compromise: a complete, ready-for-assembly set of bodywork that could be finished in any color, from the bold to the understated, while preserving the bike’s original silhouette and aerodynamics. The appeal was not merely cosmetic. The unpainted fairings offered a way to refresh aging plastics, restore an accident-damaged look, or tailor a race-inspired colorway without paying the premium of factory-painted OEM panels. The market recognized this niche and, even in Europe, a steady stream of aftermarket options began to populate catalogs and online marketplaces. Material choice mattered here as much as fitment. The standard bearer among unpainted kits was ABS plastic, chosen for its balance of impact resistance, rigidity, and light weight. ABS-based fairings can absorb a little flex without cracking, which matters when the panels must match precise mounting points across a motorcycle’s frame and substructure. The engineering behind these kits aims to reproduce the factory geometry so the mounting holes align with the bike’s original hardware, the headlight and instrument openings align with minimal trimming, and the air ducts and ram-air intakes sit in their intended positions. It is a careful dance between form and function, where the paint is a canvas and the underlying shape is the performance backbone. The kits are typically presented as full-body replacements, intended to restore a bike to its original visual heft while enabling unique color choices long after the showroom finish has faded or the original color has fallen out of fashion. In the European market of the mid-2000s, the availability of such unpainted sets reflected a broader shift toward accessible customization. Riders who wanted a custom look but did not want to invest in licensed, OEM-painted panels found the unpainted route appealing. They could prepare the surface properly, prime it, lay down a base color, and apply topcoats and clear finishes that delivered the exact hue and gloss they imagined. This approach aligned with a rising DIY ethos in motorcycle culture, where hands-on care and personal design were celebrated as much as speed and torque. As a result, the aftermarket ecosystem grew to include suppliers who produced complete kits tailored to European 2006 specifications. A typical kit would include front and rear fairings, side panels, belly pans, and sometimes a subframe cover, with mounting hardware and seals designed to sit close to the original parts. The emphasis was on a clean, factory-like fitment, so the consumer would face minimal alignment issues during installation. The market’s clarity on what “unpainted” implied helped manage expectations: you were buying a new set of panels that could be customized, not a salvaged collection of mismatched pieces. For riders new to this approach, the decision often boiled down to fitment accuracy, finish quality of the plastic, weight considerations, and the total cost compared with OEM replacements or repaints. It is here that the European scene shows its character: buyers valued compatibility with European-spec bikes and the ability to source complete bodywork without the constraints of regional distribution networks. In this context, a widely circulated listing on a major marketplace offered an unpainted naked fairing kit designed for the 2006-2007 generation of a popular European sportbike family. The listing advertised a full bodywork solution in unpainted ABS plastic, designed to accommodate the bike’s unique curves and mounting points while allowing the new owner to personalize the finish. For those who want to see how such a kit is described and positioned in the market, the following example provides a sense of the typical product narrative and practical expectations: Unpainted Naked Fairings Plastic for Suzuki GSXR 600 750 2006 2007 K6 Bodywork. This link illustrates how the market framed these products: full kits sold as brand-new aftermarket bodywork, unpainted, with the promise of a precise fit and a canvas for customization. While the specific model references in this context point to a familiar European sportbike lineage, the underlying pattern was broadly applicable across several 2006 European-spec machines, where owners could swap entire panels rather than patch from damaged segments. The emphasis remained consistent: you could restore the bike’s silhouette, refresh its surface, and then claim a color story that matched your personal road narrative. The practical implications of this choice extended beyond aesthetics. The unpainted fairings often arrived with all the necessary cutouts aligned, reducing the need for costly modifications. However, this does not eliminate the due diligence required. Fitment checks before painting are essential. A careful buyer would compare the kit’s mounting points to the bike’s frame, verify the alignment of the headlight and air intake channels, and inspect the edge finishes along each panel. Some European owners found that minor trimming or sanding, along with precise torqueing of fasteners, was necessary to achieve a seamless result. The project thus became a part of the ownership experience—a blend of mechanical care and artistic planning. The broader European aftermarket ecosystem in 2006 also included kits for other popular models and years. While the GSXR family from that era is often cited due to its enduring popularity, the same unpainted approach extended to other touring and sport configurations. The philosophy was consistent: minimize downtime, maximize customization potential, and preserve or enhance the machine’s aesthetic language. In this environment, buyers tended to seek vendors with proven track records for accurate fitment and reliable packaging. They preferred sellers who provided clear diagrams, precise measurement guidelines, and photographs that conveyed the panel geometry from multiple angles. The art of choosing an unpainted kit was as much about the storytelling of the bike’s future appearance as it was about the mechanical fit. It is also worth noting that the decision to go with an unpainted kit can interact with regional regulations and practical realities of ownership. European riders often navigate stricter color-matching expectations for certain event appearances, the potential need for local paint shops, and the logistics of shipping heavy plastic components across borders. While these challenges exist, the market’s resilience in 2006 indicates a strong appetite for customization that could be integrated into a rider’s schedule and budget. The unpainted approach offered a predictable, repeatable process: purchase, inspect, prepare the surface, apply primer, paint the base color, finish with a clear coat, and assemble. For those who value a personalized finish that reflects a rider’s individual identity as much as the bike’s performance, unpainted fairings provided a practical path to achieve both. The narrative of 2006 European unpainted fairings is not a tale of a single model or a single country; it is a snapshot of a broader culture in which riders embraced DIY artistry as a complement to the engineering mastery on two wheels. The aftermarkets in Europe were proactive in compiling complete kits, clarifying fit, and supporting the painter’s journey with reliable materials and documented assembly guidance. This ecosystem enabled enthusiasts to pursue a palette that matched regional tastes and personal stories—whether their palette leaned toward the classic, understated tones or toward aggressive, race-inspired contrasts. For those who want to delve deeper into how unpainted fairings are positioned in the market and what buyers should expect, the general takeaway is that these products exist at the intersection of fit, finish, and feasibility. They are not mere shells but functional canvases designed to preserve the bike’s geometry and aerodynamics while unlocking an opportunity for aesthetic invention. As the chapter turns toward other chapters that explore the broader implications of aftermarket bodywork, it becomes clear that the 2006 European market was a crucible for a modern approach to customization—one where do-it-yourself painters could imagine a color story without being tethered to factory paint schedules or exorbitant OEM pricing. The journey from a bare, unpainted fairing kit to a finished, gallery-worthy motorcycle reflects a broader shift in how riders engage with their machines: not merely as assemblages of speed and torque but as expressive canvases that move in harmony with the road. External resources provide broader context for those who wish to understand the technical and cultural layers of this practice. For a wider look at unpainted fairings in the contemporary aftermarket space, see this external reference: https://www.aliexpress.com/item/1005002494852483.html

null

null

Final thoughts

The exploration of 2006 European motorcycle unpainted fairings reveals a treasure trove of possibilities for both performance enhancements and personal expression. Knowing the specifications ensures you can confidently recommend suitable options to customers, while understanding market availability aids in sourcing the right products. Further, embracing customization opens pathways to greater customer satisfaction and loyalty. As businesses adapt to these offerings, the potential for growth in sales and customer engagement can significantly increase.