The racing scene of the 1960s heralded a pivotal moment in motorcycle design, highlighting the importance of fairings and cowling for both aerodynamic efficiency and aesthetic appeal. This era’s technological advancements not only revolutionized performance on racetracks but also shaped the culture surrounding motorcycle racing. Fairings made from fiberglass began redefining not just the speed capabilities of motorcycles, but also the visual identity of racing machines. In this exploration, we will delve into three key chapters that each provide insight into the multifaceted role of fairing cowling: the technological innovations that drove performance, the cultural impact these enhancements had on motorcycle design, and the economic implications woven into this thrilling chapter of racing history.

Wings on the Wind: How 1960s Race Motorcycle Fairings Rewrote Speed, Handling, and Style

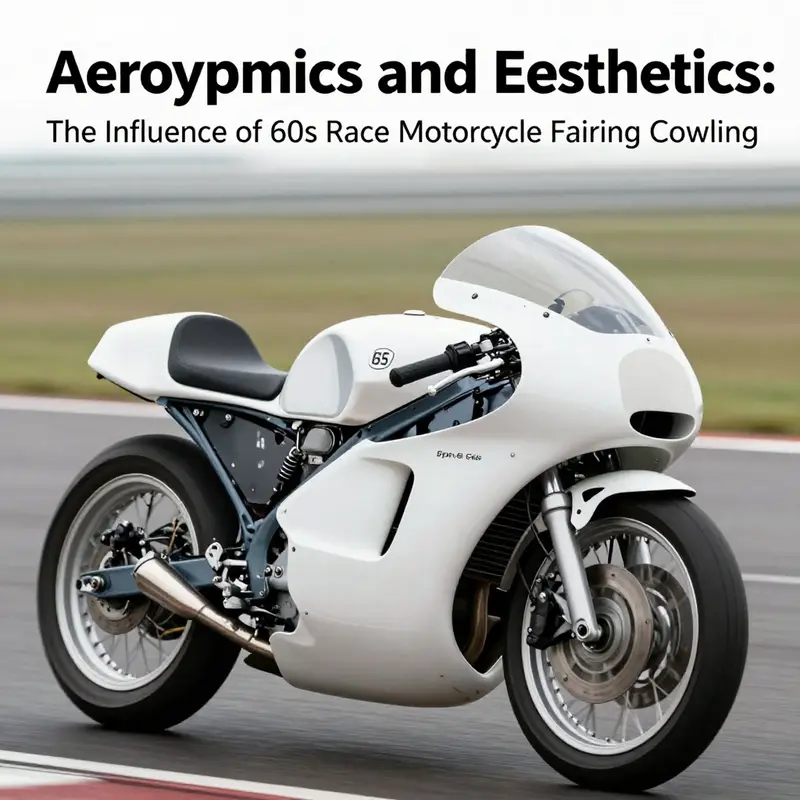

Air became a rider as much as a rival on the track in the 1960s, when engineers and riders learned that the shape and shell surrounding a machine could matter as much as the engine it housed. The race against air began with a stubborn truth: air does not simply surround a bike; it presses, pulls, and nudges from every angle, shaping how quickly a motorcycle can accelerate, how steadily it can bisect a straight, and how cruelly it can buffet a rider at the edge of control. The introduction of fairings and cowlings—thin, carefully shaped shells designed to manage the air—marked a turning point in that ongoing dialogue between speed and surfaces. These shells, often made from fiberglass, offered a crucial combination: weight savings that did not demand extraordinary compromises in strength, and a sculpted form that could slice through air with less resistance than the naked frame it couched. The 1960s, in particular, were a laboratory of trial and error, a proving ground where aesthetics and aerodynamics constrained each other in equal measure, and where the line between race chassis and wind tunnel became increasingly blurred.

Fiberglass arrived as the material with the right balance of pliancy and stiffness for a world in which every gram mattered and every gust could decide a race. It was light enough to tilt the scales toward higher top speeds and quickened steering responses, yet robust enough to survive the occasional collision with a hay bale of wind or a bracing gust that toppled a less forgiving shell. The shift from heavier metals and wood to fiberglass did more than shave weight; it opened a new realm of freedom for shaping. Designers could create more slender noses and tighter transitions, blending the rider’s silhouette with a continuous air path that began at the leading edge and wrapped toward the tail. It was, in effect, a move from a bare frame to a narrative of air: the fairing telling wind where to go, and the rider’s body becoming part of that story rather than a passenger to it.

This era’s fiberglass fairings often found their most visible early expression on a classic, compact twin that dominated many circuits with its unbeatable torque and lively steering. The shell fitted around the engine, the cylinder blocks, and the down tubes with a confidence that suggested a new partnership between rider and machine. The look was unmistakably period: a sweeping, narrow nose, a cockpit that hugged the rider’s chest and forearms, and a rear section that tucked behind the rider’s back like a whispered suggestion of speed rather than a blunt statement of power. The visual language of the 60s fairing—smooth, elongated, almost sculpture-like—read as a manifesto: speed could be made legible, almost legibly in the way light runs along a curved surface. Yet for all their elegance, these early shells were not yet the final word in aerodynamics. They were the first steps in a long conversation, and they bore the signatures of improvisation and rapid iteration. Mounting a fairing was rarely a plug-and-play affair; fitment kits were often bespoke or cobbled from a patchwork of brackets, clamps, and careful measurements. What worked on one machine might require radical modification on another, a reminder that the 60s culture of racing prized ingenuity and adaptability as much as it did raw speed.

Material choices in these early shells mattered as much as the lines themselves. Fiberglass offered the most accessible path to a lighter, workable shell, but it also imposed limits. The layup process was labor-intensive, frequently done by hand, and the tolerances were not yet standardized across manufacturers or even across racing teams. This meant that aerodynamics could vary not only from model to model but from race to race, as sheets of fiberglass were molded to fit the exact curvature of a particular chassis. The result was a landscape where every shell carried a fingerprint of its maker, its model, and the race it was designed to conquer. The shapes that emerged were not merely about sleekness; they were about balance—the balance between reducing drag and maintaining enough wind protection to keep a rider focused and in a sustainable position at high speed. In practice, the aim was to minimize lift and drag while keeping the rider’s head and chest shielded from the worst of the wind pressure. Yet the wind did not yield easily. At high speeds, air tends to find leaks and seams, and even the most carefully contoured fairing could become a source of buffeting if the rider’s helmet or shoulders disrupted the airflow in unpredictable ways. These are the kind of trade-offs that defined the era: every gain in one direction carried a potential cost in another, and the skill of the crew lay in navigating those compromises with an eye toward the next race.

Aesthetics and function walked hand in hand. The visual appeal of a fairing in the 60s was inseparable from its performance narrative. A well-proportioned shell appeared to be in dialogue with the machine’s philosophy: a factory-driven sense of purpose that looked equally at speed and control. The elongated lines, the gentle taper toward the tail, and the way the cockpit nestled behind the wind with a rider’s shoulders barely breaking the surface all spoke to a broader design language that would permeate motorcycle aesthetics for years to come. The on-track reality, however, often tested these ideals. The rider’s cockpit could become a narrow corridor where elbows and forearms learned to wedge into position with precision, and the curious interplay between glove and fairing could either smooth the flow or invite friction. Some shells offered surprisingly good wind protection at the speed sweet spot, while others good-naturedly spared the rider a brutal draft only to expose the torso to a harsher wind at different yaw angles. The variability is telling: it underscores how the era’s engineers chased a moving target—drag coefficients that could be reduced by inches yet translate into meaningful improvements only when integrated with the bike’s geometry, rider position, and even tire behavior on the track.

This was a period of rapid transition, not only in materials and forms but in the culture surrounding the sport. The fairing ceased to be a mere functional cover and began to embody a broader commitment to specialization within racing. The shell became a visible symbol of how teams approached performance as a holistic system: the chassis, the engine, the aerodynamics, and the rider’s technique all synchronized through the fairing’s contour. In this sense, fairings helped magnetize a new culture of design in motorcycle racing—an awareness that the machine’s outer skin could be engineered with as much intellectual care as its internals. The practicality of a fairing—protecting the rider from wind-blast and debris while offering nearer to a wind trap around the rider’s torso—was balanced against concerns about maneuverability and maintenance. A fairing that was too integrated with the frame could hamper quick adjustments in a pit where every second counted, while one that was too modular risked losing the aerodynamic cohesion that a well-integrated shell could provide.

In the broader arc of 1960s competition, the fairing’s utility extended beyond mere speed advantages. The shells allowed teams to experiment with rider positioning with a new kind of confidence. The rider could ride with greater certainty at high speed because the fairing’s air path was designed to stabilize flow around the machine, reducing vexing crosswinds and the unpredictable buffet that can unsettle a rider at the apex of a corner. The design language also contributed to a distinct visual identity for the era’s race machines. The fairing’s lines spoke of a time when motorcycles were both machines of culture and devices of performance. The aesthetics, while rooted in function, carried with them the era’s sense that speed was a coordinated performance between human and machine, one that could be improved through thoughtful shaping of the air’s routes.

Behind the scenes, the development of fairings in the 60s also raised tensions between universality and customization. The lack of standardized fitment across different models meant that teams often built or adapted shells to their exact machines. The same shape that helped a particular twin slice through air on one circuit might feel awkward on another machine with slightly different chassis geometry. In practice, racers and engineers learned to view the fairing not as a one-size-fits-all accessory but as a bespoke element that could be tuned to the bike’s personality and the demands of a given track. This bespoke attitude helped foster a culture of craft in racing, where small teams could produce meaningful performance differentials through careful shaping, precise mounting, and a willingness to experiment with interior wind paths, air vents, and cockpit fairing cutouts. Even with the limitations of the era’s materials and tooling, the pioneers of fiberglass fairings demonstrated that a well-conceived shell could be a decisive asset in a sport where margins between victory and second place were measured in seconds and, sometimes, fractions of seconds.

The narrative of the 60s fairing is also a reminder of how technology travels. What began as a lightweight shell for wind protection and drag reduction gradually evolved into a tool for speed discipline that would shape racing for decades. The early, rudimentary fairings were stepping stones—proof that aerodynamics could be translated into tangible, track-ready improvements even when the science of airflow and materials science was still maturing. The lessons learned—about how to balance drag reduction with rider protection, about how to mount and adapt shells across a range of machines, and about how to manage the interplay of human and machine in a confined cockpit—became the underpinnings for later innovations. By the time the 70s and 80s rolled around, the concept of a dedicated fairing had become standard practice, even though the shapes would continue to refine toward more sophisticated computationally informed profiles. The 60s era, with its fiberglass shells and brave experimentation, thus sits at a crucial hinge: it is the moment when the track’s tempo demanded more than brute engine power; it demanded a coherent aerodynamic philosophy and a new aesthetic language that could communicate speed as much as confer it.

For readers curious about how these early designs relate to modern interpretations of fairings, a broader historical perspective can be found in resources that explore the mechanical properties and usage strategies of mid-century and later fairings. See the Z650 fairings guide for a detailed context on how older concepts evolved into more contemporary forms, and how material choices and design constraints influenced both performance and maintenance on modern machines: Z650 Fairings: Types, Mechanical Properties, and How to Use Them Effectively.

As the decades progressed, the lineage of these early shells would fuel a more systematic approach to aerodynamics in racing bikes. The 60s fairing narrative is not merely about the moment when fiberglass first wrapped around a bike; it is about recognizing how that shell made riders braver and teams more methodical. The wind, once a simple adversary to beat, became a collaborator to exploit—its forces harnessed through curves, bulges, and carefully placed camber that guided air along advantageous paths while preserving rider control. That was the essence of the transformation: a mechanical embrace of air that translated into tangible track performance, a design philosophy that saw form as a function and function as a form, and a visual identity that told spectators and engineers alike that speed was now a field of intelligent, collaborative craft rather than a purely muscular contest of torque and horsepower. The 1960s fairing era thus stands as a foundational chapter in the long story of how race motorcycles became faster not just by pushing harder on the engine, but by making the wind their ally through calculation, craftsmanship, and a growing culture of design-in-performance.

Internal link for further exploration: Honda fairings collection.

External resource for deeper technical context: Z650 Fairings: Types, Mechanical Properties, and How to Use Them Effectively.

Wings of Speed: How 60s Race Fairings Rewired Culture and the Motorcycle Aesthetic

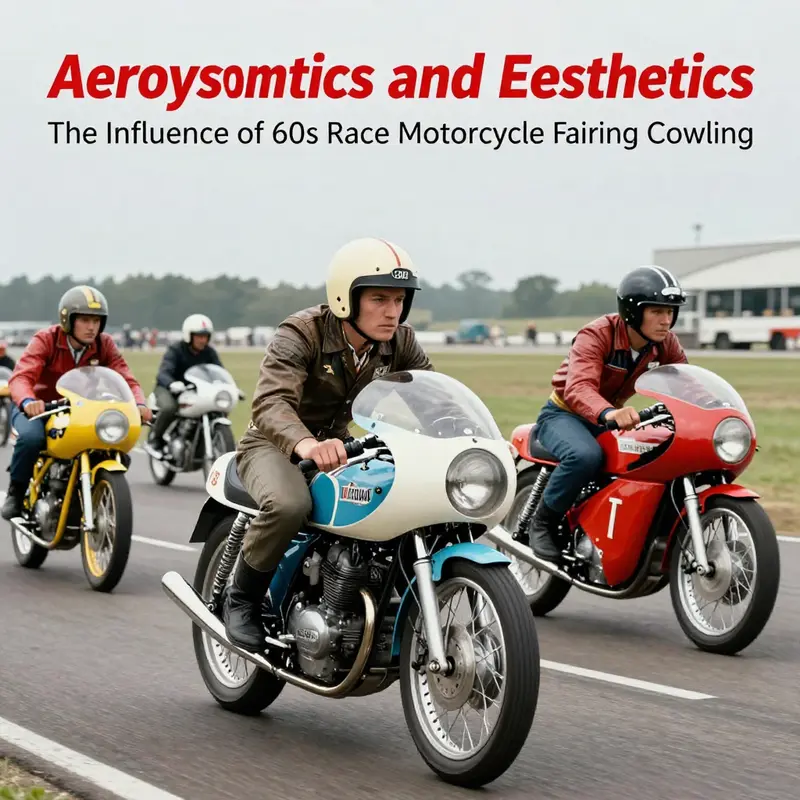

The wind-torn decade of the sixties carried not just music and rebellion but a quiet engineering revolution on two wheels. Fairings and cowling appeared not as mere add-ons but as statements about what ridership could become when speed and design spoke a common language. These early shells were built from lightweight materials, with fiberglass becoming a practical medium for shaping air and rider together into a single, efficient silhouette. In the glare of Grand Prix circuits and the glow of urban streets, the fairing became more than a shield against the wind; it was a signpost for a new culture of velocity, a visual manifesto that linked the rider’s courage to the machine’s engineered elegance. The transformation was as much about form as it was about function, a fusion of aerodynamics, craftsmanship, and a rising appetite for individual expression that would leave an imprint on how people thought about speed, design, and the motorcycle as an extension of self.

From the honest, brutal math of drag to the more subjective theatre of racing aesthetics, fairings in the 1960s embodied a shift in priorities. Engineers learned to sculpt air in the same breath they sculpted a rider’s posture, turning a rider into less of a silhouette and more of a streamlined figure in a wind tunnel’s own language. The shapes grew leaner, the lines more purposeful, and the bike’s profile became a signature—identifiable not just in the paddock but in magazines, posters, and the heady atmosphere of youth culture. The visual grammar of the era—sharp noses, teardrop shells, and bold, clean curves—began to translate from the race track into the street, identifying a rider not merely by what they rode but by how the machine looked as it moved. These were aesthetics born of necessity, yet they quickly accrued cultural resonance beyond the raceway.

The fairing’s impact extended far beyond its contribution to top speed. As a rider was cocooned behind a curved glass or fiberglass shell, the experience of the ride changed. The rider’s silhouette merged with the bike’s line, a visual metaphor for the era’s shifting sense of self-reliance and individualism. In a society that increasingly celebrated speed as freedom, the fairing underscored the belief that engineering could empower personal expression. The result was not simply a more efficient machine but a look—a look that suggested, with quiet confidence, that speed could be stylish and disciplined at the same time. This dual promise helped propel the cafe racer movement, where urban riders took race-inspired lines and applied them to the street, turning everyday commuting into a narrative about purpose and ambition. The café racer scene, with its modified frames and minimal riders’ protection, still carried the fairing’s DNA, blending rebellion with a disciplined appreciation for aerodynamics.

What began as a practical measure to reduce drag quickly morphed into a cultural shorthand. The visual language of the period—cowlings that swept back toward the rider, head fairings that narrowed the forward field of view, and svelte profiles that hinted at the bike’s power—became the standard by which speed was read. A motorcycle with a streamlined shell signaled intention: this was a machine built to cut through air, to cut through hesitation, to pursue the edge. In magazines and on movie screens, the fairing’s silhouette appeared as a symbol of modernity, a visual cue that riding could be both thrilling and aesthetically disciplined. The integration of form and function helped normalize the idea that motorcycles could be crafted with the same attention to design as cars, and that technology could be a central facet of personal style rather than an afterthought.

Cultural memory is rich with the footprints of those early fairings. They traveled from the racetrack’s bright lights to the everyday road, influencing how riders chose to present themselves. The teardrop profile, the gently curved side panels, and the shield-like front fairing became a design language that enthusiasts carried into workshops and garages. It was not just about making a bike faster; it was about making a bike a statement. The fairing’s lines spoke to a generation that valued speed as an antidote to constraint and a means of self-definition. In this way, the fairing helped sculpt a broader social arc: the rise of a youth culture that saw technology not as a barrier but as a language, one that could be learned and spoken through the careful selection and customization of parts. The results were visible in gatherings, street performances, and a torrent of imagery that celebrated the bike as both machine and cultural artifact.

The aesthetic influence stretched into civilian motorcycles as well. Enthusiasts who wanted a more race-inspired presence on the street adopted fairings to achieve a cleaner, more aerodynamic silhouette. The modifications reflected a desire to bridge the gap between the racetrack and the road, to render daily travel into a dynamic experience. Fairings did not merely serve the track; they educated a broader audience about what speed could look like. The idea that shape could influence speed became a shared belief among riders, designers, and fans. This belief fed into a design ethos that would continue to evolve in the decades to come, keeping the spirit of the 60s alive in new forms of performance aesthetics.

Beyond engineering and design, the fairing’s cultural footprint touched music, fashion, and film. The imagery of a sleek, wind-cut silhouette resonated with song lyrics and album art, becoming a shorthand for urban modernity and youthful energy. Fashion embraced the sense of motion suggested by the sleek lines; fabrics and jackets that echoed those curves appeared in street styles, aligning personal style with the machine’s language of speed. In cinema and television, motorcycles with such lines often played up the fantasy of effortless velocity—the rider as a figure moving through space with precision and poise. The fairing thus helped knit motorcycle culture into the wider tapestry of 1960s popular culture, making it legible to audiences who might never have ridden a race machine but who could recognize and relate to its aesthetic cues.

At a functional level, the fairing also contributed to the culture of racecraft. The aerodynamic gains supported faster lap times and more controlled handling, which in turn fed the rider’s confidence and competitive spirit. Yet the story was not purely about performance metrics. The pursuit of better aerodynamics encouraged designers and riders to experiment, to push boundaries, and to share knowledge across borders. The exchange of ideas—between engineers on factory floors, private tuners in backyards, and riders swapping tips in paddock conversations—helped accelerate the evolution of motorcycle technology. That exchange contributed to a sense of global community among enthusiasts who spoke a common visual and technical language, even when they spoke different dialects of engineering or rode bikes with distinct regional characters. In short, the fairing became a shared vocabulary that helped knit together a diverse but connected world of riders.

The practical realities of production during the era also played a role in shaping the cultural narrative. Materials like fiberglass offered a balance of lightness and workability, allowing makers to craft shells that could be produced with the tooling available at the time. The fairness of their production did not just serve speed; it made the dream of a race-ready bike more accessible to enthusiasts who could patch, sand, and paint a shell in a home workshop. This democratization of performance, enabled by the use of accessible materials, helped fuel the culture of customization that would become a hallmark of the era. Riders could express personal taste through paint, trim, and fairing shapes, turning each machine into a personal canvas that still bore the unmistakable signature of its aerodynamic lineage. The resulting culture was a blend of factory precision and amateur invention, a hybrid that reflected both respect for high-speed discipline and a youthful urge to reinterpret it through individual art and craft.

As the decade wore on, the fairing’s cultural significance deepened. It remained not only a protective enclosure but a banner under which a community could rally. In gatherings and races, riders with fairings presented themselves as practitioners of a refined craft, people who respected the wind as a partner rather than an adversary. The fairing’s role in shaping this identity was reinforced by the broader storytelling of the era—films featuring speed, fashion editorials celebrating clean, aerodynamic lines, and music that captured the exhilaration of streamlined motion. The fairing thus became a cultural artifact that carried the values of speed, precision, and a certain rebellion against the ordinary. It stood at the intersection of science and style, where engineering decisions were as legible as fashion choices, and where a single shell could carry a century of aspirations about mobility and freedom.

Looking back, the fairing’s cultural ripple continues to influence contemporary design and culture in ways that are less obvious but no less real. The enduring emphasis on clean lines, slender profiles, and a rider-focused silhouette demonstrates how deeply the 60s fairings embedded themselves into the modern motorcycle’s DNA. Designers still borrow the spirit of that era when shaping new aerodynamic shells, balancing the demands of wind resistance with the rider’s comfort and the bike’s visual presence. The legacy is visible in modern race machines and in the street bikes that borrow a hint of that racing aesthetic for urban sophistication. The fairing’s memory informs how new generations imagine speed—not merely as a numeric top speed but as a holistic experience that blends engineering excellence with a culture of self-expression, community, and shared fascination with the wind.

For readers seeking a deeper historical and design-focused exploration of how early fairings shaped racing culture and the broader design language of motorcycles, a detailed account is available at the external resource linked here. This broader context helps place the 1960s innovations within the long arc of motorcycle development and cultural adaptation. In particular, the shift from utilitarian shielding to sculptural speed reveals how engineering choices resonate in cultural forms, influencing everything from consumer aesthetics to rider communities and beyond.

To connect this discussion with ongoing interest in fairing design and customization, contemporary enthusiasts may explore one curated collection that highlights how modern recreations and reinterpretations keep the spirit of the era alive. The collection offers a sense of how classic lines endure, translated for today’s riders while preserving the visual cues that defined an era of wind and wonder. See the Honda fairings collection for a representative view of how archival aesthetics are reimagined for current machines, illustrating the continuity between past and present in the world of motorcycle fairings. Honda fairings collection.

For those who wish to situate these discussions within a wider historiographic framework, the following external resource provides a focused examination of the 60s race fairings culture, their social ramifications, and their enduring legacies. It situates the design revolution within the social currents of the decade, offering complementary perspectives on how technology and youth culture intersected to reshape riding as a form of cultural practice. External resource: https://www.motorcyclehistory.org/60s-race-fairings-culture

Gossamer Shields and Heavy Bills: The Economic Awakening of 1960s Race Motorcycle Fairings

In the wind-streaked arenas of the 1960s, speed on the race track was no longer the sole measure of a machine’s worth. Engineers and fabricators learned to treat air as a competitor just as formidable as any rival on two wheels. The race to the apex was joined by a different kind of contest, one that pressed the needle at the intersection of performance, manufacture, and money. The fairing cowling—once a simple shell hung over the engine—emerged in this era as a primary instrument of speed. It wrapped the rider in a protective, aerodynamically attuned skin, yet it did so at a cost that was often more than a rider’s paycheck could easily bear. The 1960s marked a turning point when the pursuit of lower drag and higher stability began to carry tangible price tags, and those costs did more than shape a single season; they helped recalibrate what racing, and later consumer sport, could become.

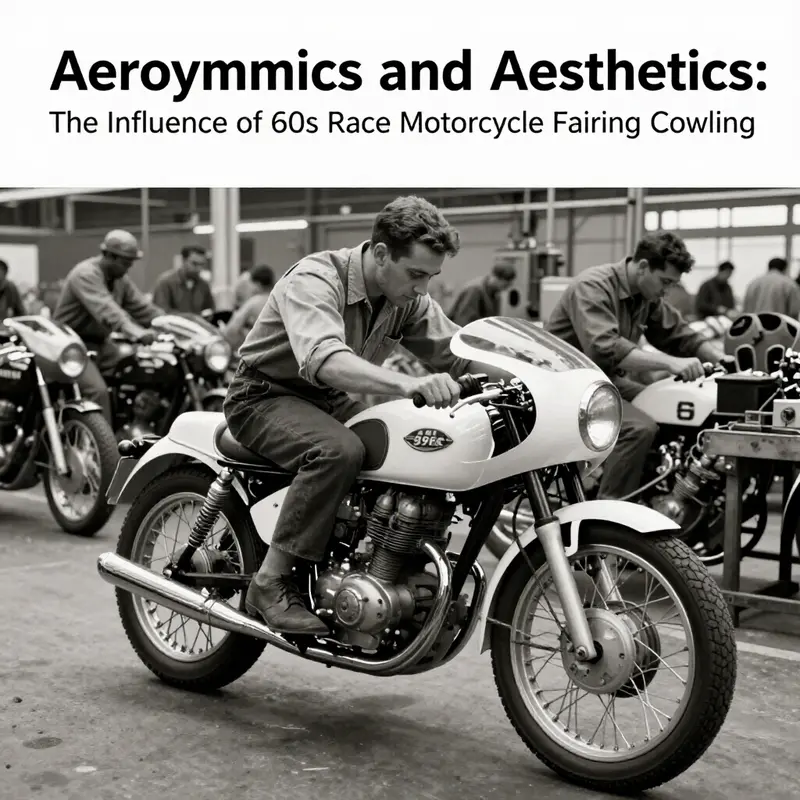

The earliest fairings of this period were less about commerce and more about craft. They were primarily fiberglass shells, born of meticulous handwork and the stubborn demand for performance. Each component was typically handmade, requiring skilled labor, patient mold work, and iterative shaping that could eat into time and budget. The materials themselves—fiberglass and simple resins—though robust for their era, demanded careful, costly labor to achieve the smooth, precise surfaces that aerodynamics demanded. The result was performance gains, yes, but with a price that reflected the realities of small-scale production. The teams that found value in these shells were often professional outfits or well-capitalized manufacturers who could absorb the risk and the expense while chasing a slim margin of superiority on the stopwatch. In other words, the 60s fairing was as much a statement of engineering of the moment as it was a statement about the economics of racing.

A central consequence of this setup was that the fairing’s cost constrained its diffusion. It was not something a casual rider could purchase or retrofit with the same willingness to pay. The production process, though increasingly sophisticated in concept, remained anchored in a world where each unit bore the stamp of a small crafts workshop rather than a mass-production line. The economic logic was straightforward in the most practical terms: if the drag reduction and rider protection could shave precious seconds from the lap time, the investment could be justified. But the same equation also meant that only the most committed teams and the most sumptuous factory programs could justify the expense each season. The market, in turn, reflected this reality with a distinct hierarchy. The cutting-edge shells were the preserve of professional crews and top-tier manufacturers, while more modest outfits relied on lighter, simpler, or later, more economical alternatives. The fairing thus did not merely shield the rider or shape the bike’s silhouette. It defined a class, created a barrier to entry, and helped anchor a commercial ecosystem in which the value of speed was measured not only in seconds but in the willingness to fund the work that made those seconds count.

In this environment, a fundamental tension emerged: the engineering ambition to minimize drag and maximize stability versus the economic need to keep production and development within reachable bounds. Aerodynamics promised gains in top speed and cornering confidence, but the early routes to those gains required materials, tooling, and craftsmanship that added up quickly. Fiberglass, while lighter than many competing approaches of the era, was not a free resource. Its manufacture demanded precise layups, careful curing, and repairs that could vary from part to part. A fairing could reduce parasitic drag, but if it weighed too much or required significant maintenance, its net benefit could be compromised. Designers learned to balance these factors in small, iterative steps, which meant that development cycles were measured in months rather than quarters. The net effect was a design language that prioritized airflow and rider ergonomics in equal measure, but always with an eye on the bottom line. Costs were not merely line items on a budget; they were active constraints that steered the shape, thickness, and attachment methods of the shell. The result was a generation of fairings that looked as if they were sculpted for speed and tested for economy, a paradox that lay at the heart of the era’s economic awakening.

Historically, this was also the era when the racing calendar and the industrial calendar began to align in meaningful ways. Sponsorships, prize money, and the visibility of a competitive program depended on performance but also on the ability to translate that performance into market credibility. The fairing’s value proposition was twofold: it offered measurable on-track advantages and signaled technical sophistication, a status that teams could market to sponsors and fans alike. The narrative around the fairing evolved from a purely technical feature to a symbol of a team’s commitment to cutting-edge engineering. That symbolism carried economic implications. The more a shell could convincingly deliver both on speed and style, the more likely it was to attract investment, secure development funding, and justify the heavy costs embedded in its design and production. The fairing became a vehicle for telling a broader story about a team’s technical ambitions, one that investors could measure as surely as lap times.

The economic texture of this period extended beyond the factory floor. A fairing’s cost influenced decisions about which races to pursue, which tracks to prioritize, and how to approach the delicate issue of rider safety. Protective qualities, while essential, did not exist in a vacuum. A well-designed shell could reduce rider fatigue by offering a more stable cockpit and minimizing buffeting at high speeds. Less fatigue meant better performance across a race distance, which, in turn, affected a team’s ability to remain competitive from one event to the next. Yet the same protective features, if implemented with excessive weight or rigidity, could undermine handling and cornering, particularly on circuits with lower speed and tighter turns. Here again, the economic calculus mattered. Teams weighed the benefits of advanced shells against the realities of tire wear, fuel consumption, and the costs of reworking parts after crashes or practice sessions. In practice, this meant that a fairing’s design had to deliver a net performance increase that justified its price tag and its maintenance cost.

In the broader industry, the mid-century shift toward specialized components foreshadowed a transformation that would unfold over subsequent decades. The 60s fairings were among the first components to illustrate that performance could be engineered into every facet of the machine, not just the engine or the frame. This mindset seeded a gradual expansion of the market for high-performance accessories, setting the stage for a more structured supply chain later on. The fairing began to anchor a spectrum of automotive tooling and materials development, from mold-making techniques to resin chemistry and surface finishing. The reputational value of a successful fairing project extended beyond one race season; it carried through to subsequent model generations, a pipeline of knowledge that could be reworked, refined, and adapted to new mechanical configurations. The result was an emergent sense that the racing oval was a test bed not only for speed but for the alloys, composites, and manufacturing know-how that would eventually populate the consumer market.

From a design perspective, the early fairings were celebrated for their form as much as their function. The aesthetic language of wind-cheating geometry—slopes and fillets calibrated to create smooth transitions for the air—emerged as a visual shorthand for efficiency. The racing paddock became a living laboratory where form followed the demands of physics, and where teams rewarded those who could translate theoretical drag reductions into tangible lap-time improvements. Aesthetics thus acquired a practical dimension; it was not vanity, but a disciplined response to a kinetic challenge. The artistry of shaping, sanding, reinforcing, and finishing a fiberglass shell became as crucial as the mathematics that predicted drag coefficients. In that sense, the 1960s fairing era helped crystallize a philosophy: speed is engineered beauty, but beauty must earn its keep at the speed the track demands. This dual obligation to performance and practicality anchored the fairing in an economic framework that valued craftsmanship while insisting that expenditures yield measurable returns.

The manufacturing realities of the time also left their mark on how teams approached development costs. Because fairings were not mass-produced, the economics favored those with the capital and organizational discipline to absorb prototypes, tests, and successive revisions. Iterative design cycles—mold making, trial assembly, on-bike testing, feedback from riders—were expensive and time-consuming, yet they were indispensable to achieving the precision required for success on the fastest circuits. In this sense, the 60s fairing story is a microcosm of a broader motor industry trend: precision engineering at a premium, a deliberate trade-off between speed and scale. The resulting balance helped shape a professional racing ecosystem where performance commitments were codified into engineering practice. And as teams refined these components, the cost structure gradually established a baseline for what subsequent generations would expect to pay for aerodynamic gain. The economic narrative thus travels forward: the technical triumphs of the 60s informed 70s and 80s development, and eventually, the consumer market began to absorb the lessons learned on the race track.

The broader market response to this shift was gradual but persistent. As the racing narrative matured, manufacturers and suppliers began to recognize the value in offering more standardized options that could bridge the gap between professional original equipment and aftermarket performance parts. The principle that performance could justify higher upfront costs proved transferable. It encouraged a diversified market in which a variety of customers—racer-enthusiasts, track-day participants, and even curious enthusiasts—could pursue enhanced aerodynamics through increasingly accessible products. The economic logic evolved from one-off, hand-built shells to a broader, more scalable architecture: a product category that could be refined, scaled, and marketed without sacrificing the core engineering truth that aerodynamics and rider safety are inseparable allies in the pursuit of speed. In that sense, the era did not simply produce better shells for better times; it seeded a commercialization pathway that connected the paddock to the showroom, ensuring that the value created on the track would resonate in the wider world of motorcycling.

Yet the period’s economic awakening was not merely a tale of rising budgets and broader distribution. It was also a reminder that innovation has asymmetries in cost and benefit. The most effective aerodynamic gains often came at the expense of weight, stiffness, or ease of maintenance. The political economy of racing—teams, sponsors, and event organizers—therefore pushed designers to identify sweet spots where the aerodynamic uplift would not be overshadowed by penalties in handling, durability, or serviceability. This balancing act required disciplined trade-offs, and it was here that the financial dimensions of the problem most clearly manifested. The designs that endured over multiple seasons were the ones that could survive the grind of practice, qualifying, racing, and post-race repair within the limits of a competitive budget. In a world where every practical improvement carried a price tag, the fairing emerged as a test case for how far a sport could push the envelope without decoupling speed from economic viability.

On the cultural side, the rising costs and the need for specialized knowledge helped cultivate a distinctive collector of skills within the paddock. The craft of shaping, reinforcing, and finishing a fairing was a savoir-faire that included mold building, composite layups, fiberglass repair, and paintwork. It gave technicians a valued skill set that men and women could build careers around, even as the racing calendar came and went. In this way, the fairing era contributed to a broader professionalization of the sport’s technical workforce, creating a pipeline of talent that later benefited production teams and aftermarket suppliers alike. The end result was a culture where speed was inseparable from the people who made the shells, and where the material and labor costs of design—once seen as an unfortunate burden—were reframed as essential investments that underwrote future capabilities. This was not mere ornamentation; it was economic confidence that the right team with the right resources could push the limits of what a two-wheeled machine might endure on a high-speed circuit.

As the decade wore on, the fairing’s role in the industry’s evolving structure became clearer. The wake of this period left a trail of design heuristics and material experiences that would be revisited and reinterpreted as technology advanced. Contemporary riders may enjoy sophisticated, lightweight composite shells with careful attention to fatigue resistance and crashworthiness, but the 1960s fairing taught a different lesson: the best aerodynamic solution is the one that a team can conceive, craft, test, and sustain within its financial means. That lesson persisted in consumer markets as well, where a more standardized set of parts and services eventually allowed a broader cohort of riders to engage in performance-enhancing customization. The transition from bespoke, high-cost components to more accessible, scalable options did not erase the underlying tension between speed and spend; it reframed it. It became a question of how to deliver meaningful gains in perfomance while maintaining a business model that could nurture innovation without bankrupting those who chased the next improvement. The fairing’s economic story thus bridged the paddock’s urgency for speed with a market’s need for sustainability, creating a blueprint that continues to inform the evolution of aerodynamics in motorcycles today.

The narrative of 1960s race fairings also invites reflection on the broader arc of technology diffusion in sport. What began as a specialized measure for the elite racer gradually seeped into the wider culture as consumer interest and industrial capacity grew. The fairing’s credibility as a technology intensified as data and experience accumulated: every new shape could be assessed not only by how it felt on the track but by the statistics it produced in wind tunnel tests, on-board telemetry, and pit-side observations. The knowledge base expanded from the hands of a few skilled craftsmen to a more collaborative ecosystem of designers, engineers, and suppliers who could translate the language of drag reduction into a design brief that many teams could respond to. Over time, this diffusion helped to democratize some aspects of performance, even if access to the top-level racing grade components remained restricted by cost. The enduring takeaway is that the 1960s revolution in fairings was both a technological and an economic inflection point. It redefined what counts as value in speed and catalyzed a chain reaction that shaped the way the sport and its surrounding market would operate for decades to come.

The connection to today’s world of fairings can feel distant yet it remains instructive. The economic pattern of craft, cost, and capability that characterized the 60s is echoed in every era where performance is pursued through aerodynamics. The modern market bears the imprint of those early decisions, even as it benefits from advances in materials science, production techniques, and global supply networks. High-performance shells are now less about a handful of teams chasing an edge and more about a continuum of improvement that involves manufacturers, independent designers, and a broad community of riding enthusiasts. Yet the central truth persists: the value of a fairing is not just the drag it reduces or the style it bestows. It is the sum of its performance, its durability, and its ability to be integrated into a broader business case that keeps innovation moving forward. The 1960s fairings were not merely covers for engines; they were early indicators of how technology, design, and economics could align to accelerate both sport and industry. In reading the traces of those shells, we glimpse how far the wind and the wallet can bend toward speed when a community of makers commits to a shared ambition.

For readers who want to trace the practical lineage from those early forms to modern displays of aerodynamics in accessories, the modern catalog of fairings offers a tangible lineage. A representative reference is the broader cataloging of historical and contemporary shell designs, such as the collection that gathers various shapes and styles into a coherent range. This continuum reveals how the same fundamental concerns endure: minimizing drag, protecting the rider, maintaining balance and maneuverability, and doing so within the constraints of cost and manufacturability. The conversation is ongoing, but the 60s fairing remains a crucial origin point, a moment when the wind’s whisper began to demand a budget and a plan, not merely a clever idea. The legacy is not a single shape or a single technique; it is a culture of engineering discipline, a recognition that speed is built upon the careful alignment of air, material, and money.

As you consider the broader historical arc, it is worth reflecting on how the equator of speed and technology rotated around the fairing. The shell’s evolution demonstrates that the pursuit of aerodynamic efficiency is inseparable from the economic realities that support it. Innovations may be born in wind tunnels, but they are proven in garages, in paddocks, and in the balance sheets that decide which ideas survive another season. The 1960s fairings remind us that progress in sport does not arrive at zero cost; rather, it arrives at the convergence of daring engineering and disciplined finance. And while the mechanics of this convergence have grown more complex with time, the central principle remains: if speed is the objective, the economics of achieving it must be navigated with equal care and resolve. The fairing is thus not merely a component; it is a symbol of how a sport can monetize, optimize, and ultimately democratize speed through a shared industrial journey. For those who seek to understand the modern market and its connection to racing’s past, the 1960s fairing story offers a clarifying lens. It shows how an aerodynamic idea, born in the cauldron of competition, can evolve into a universal instrument of performance, style, and value.

To explore the lineage of fairings from racing heritage toward contemporary customization in a practical, consumer-facing context, consider a representative resource that collects contemporary fairing designs and parts. This reference helps illustrate how the industry translates the lessons of the 60s into today’s modular, design-forward catalogs that riders can access. Honda fairings provides a concrete example of how modern suppliers organize and present performance-oriented shells within a broader ecosystem of riders and mechanics. While the scale and technology have shifted, the underlying logic remains consistent: aerodynamics, rider protection, and the economics of production continue to shape what is possible on two wheels.

For broader context on the sector’s economic footprint that helps frame why these discussions matter, a UK-focused economic overview offers useful perspective on how motorcycling has become woven into the fabric of industry and employment. The BBC report The Economic Impact of Motorcycling in the UK discusses the sector’s broader significance and helps situate the 60s innovations within a longer, socio-economic arc. See https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-34789012 for details.

Final thoughts

The motorcycle racing scene of the 1960s was fundamentally transformed by the advent of fairing cowling, which enhanced not only performance but also aesthetics and market dynamics. These technological advancements shaped motorcycles, reflecting a synergy of form and function that resonates even today. The cultural significance of these designs symbolizes an era where speed intertwined with style, while the economic implications indicate a burgeoning industry fueled by innovation. As we look back at this exciting chapter in motorcycle history, it becomes clear that fairings were not merely accessories but integral components that propelled the sport and motorcycle designs into new realms, leaving a lasting legacy across generations.