The motorcycle fairing represents a pivotal development in motorcycle design, enhancing both aerodynamics and rider comfort. As motorcycles transitioned from basic utilitarian machines to high-performance vehicles, the need for innovative designs became paramount. This article delves into the history and evolution of the first motorcycle fairing, examining its technological innovations, historical significance in racing, contributions from key manufacturers, and its lasting impact on contemporary motorcycle design. By analyzing these facets, business owners can appreciate the fairing’s role in optimizing performance and aesthetic appeal in today’s market.

Shaping Speed: The Birth and Rise of the First Motorcycle Fairings

The voyage toward aerodynamics began as curiosity about wind, not a blueprint for performance. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, motorcycles were essentially bicycles with engines, their silhouettes dictated by function rather than flow. Riders braced against the wind, while engineers chased reliability, torque, and efficiency, not laminar perfection. Yet as speeds climbed, wind resistance emerged as a stubborn adversary, tiring riders and stealing tempo from engines.

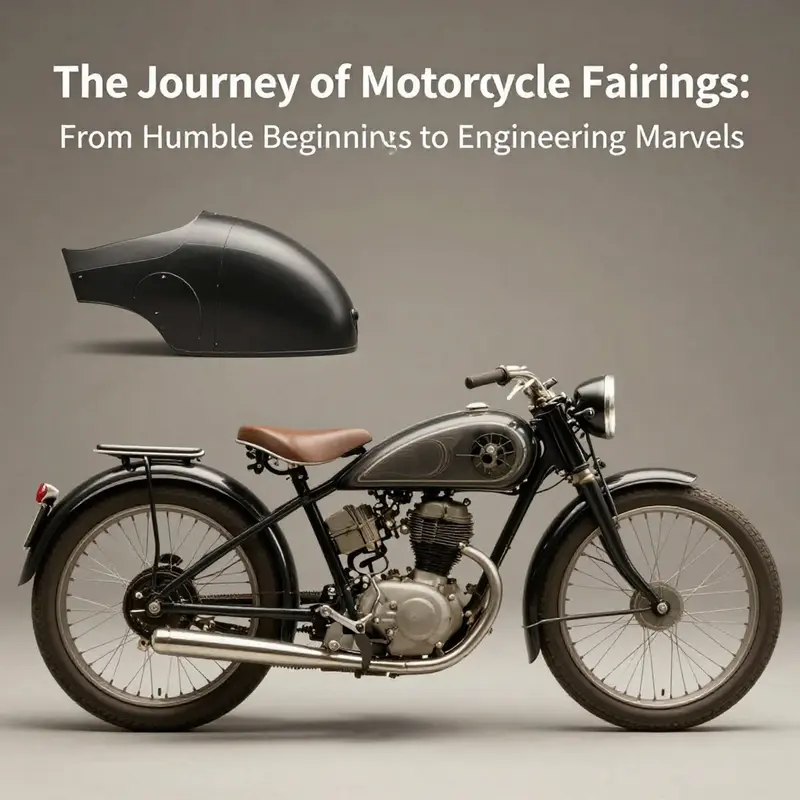

The first moves toward shielding and shaping were modest: simple plates, partial shells, little front covers that protected legs and engine parts. These were stopgap steps, not a design philosophy. The real leap came with European racing culture in the 1930s, where airflow began to be treated as an integral variable rather than a nuisance.

The Norton Manx of 1937 is often cited as among the first racing machines to feature a small, faired front end. This was more than styling; it signaled a shift toward an aerodynamic shell designed to direct air, stabilize the rider, and protect from the gusts that unsettled handling at race pace.

In the 1950s and 1960s, production and race bikes adopted full fairings. The entire front silhouette, cockpit geometry, and even the undercarriage were redesigned into a coherent package. Materials like fiberglass and aluminum supplied the shaping freedom to form continuous curves that could weather vibration while offering rider protection.

Racing then pushed the boundaries with purpose-built machines—the MV Agusta 500cc racers, among others—where fairings became platforms for downforce management, ergonomics, cooling, and predictable behavior at speed. The fairing ceased to be a cosmetic add-on and became a design variable with measurable impact on speed and stability.

As science and manufacturing matured, a feedback loop linked racing expertise to street models. Fairings moved from novelty shields to integrated aerodynamics that defined a motorcycle’s character, whether for touring, sport riding, or track work. Today catalogs trace a lineage from those early experiments to the sculpted shells shaping modern bikes, reinforcing the idea that air belongs in the design brief, not merely as a backdrop to power.

The story continues beyond history—how materials, cooling paths, and rider ergonomics converge in today’s production and aftermarket offerings. The first fairings, born to fight wind, became a central engine of speed, comfort, and control.

Racing Winds and Shaped Bodies: The Aerodynamic Leap That Gave Birth to the First Motorcycle Fairing

The story of the first motorcycle fairing unfolds not as a single instant of invention but as a gradual answering of a concrete problem: how to balance speed, control, and rider comfort as machines pushed into ever higher velocity realms. Early motorcycles grew out of practical transportation, their shapes dictated by function rather than form. Drag and windblast were tolerable nuisances at modest speeds, but as performance demanded more power and longer rides at high speed, the physics of air began to matter in new, tangible ways. Designers and engineers, observing riders steel themselves against gusts and buffeting, began to experiment with shields and covers. These early attempts were modest in scale and scope, more about shelter and line-of-sight protection than a fully integrated aerodynamic philosophy. Yet they seeded a lineage. The slow accumulation of ideas would, in the hands of racing teams and forward-thinking manufacturers, mature into the modern fairing: a full, purpose-built shell engineered to sculpt the flow of air around a moving machine and its rider.

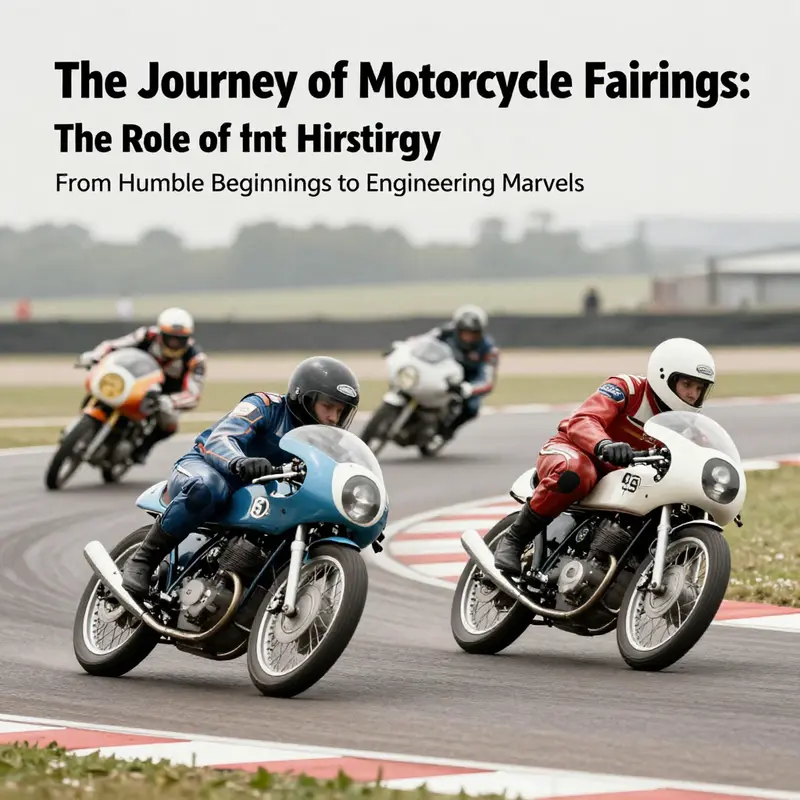

The mid-20th century marks the pivot point in this evolution. Racing, with its relentless demand for speed, stability, and efficiency, created a sandbox where aerodynamic thinking could prove its value in real terms. Designers did not simply wrap a rider in a plastic shell; they interrogated the very nature of air interacting with a motorcycle at speed. What happens when air meets a naked form? How does a shape manage separation, pressure recovery, and vortex formation behind the rider’s helmet? How can a fairing protect the rider from wind fatigue while preserving, or even enhancing, steering feel and front-end grip? Answering these questions required new materials, new manufacturing techniques, and a willingness to experiment with the silhouette of the machine itself. Lightweight composites, early fibrous laminates, and molded shells revealed that air could be guided rather than resisted, and that the rider could become part of a more efficient system rather than a burden to be buffeted by the wind.

In racing circles, the front of the bike began to resemble a small aerodynamic sculpture rather than a purely mechanical safeguard. Front panels, partial shells, and eventually full hulls began to appear on boards and race bikes. The goal was clear: reduce form drag, smooth the path of the machine through air, and improve high-speed stability. A well-designed fairing could split air more cleanly, direct it away from the rider, and tame the unpredictable gusts that arise when a machine is pressed toward the limit. The improvements were not merely about speed; they were intimately connected to handling. A rider could breathe easier, steer with more confidence, and endure the high-frequency buffeting that unsettled the best chassis at speed. When wind loads fall and downforce at the front becomes more predictable, precise control follows. This is why the early fairing development hinged on both aerodynamic theory and practical testing in harsh, real-world conditions—on race tracks under demanding conditions.

The design language of the fairing began to show a recognizable logic. Rather than a flat plate or a simple shield, the evolving shells adopted a curved, enveloping form that wrapped around the rider’s torso and, in some cases, extended toward the engine and beneath the rider’s knees. The materials expanded beyond metal into composites that could be shaped with far more freedom. The fairing emerged not as a cosmetic accessory but as a carefully tuned component of the motorcycle’s overall performance package. It needed to be strong enough to withstand debris and high-speed pressure, yet light enough not to sap performance. It had to accommodate the rider’s line of sight and control levers, provide space for instrumentation, and, crucially, offer some degree of protection from the elements while not obstructing the rider’s ability to move in the saddle. In other words, the fairing had to integrate with the geometry of the rider’s posture and the dynamics of the bike as a system.

A key insight in this historical moment was the understanding that air behaves differently around a rider depending on posture. A more tucked riding position could dramatically reduce frontal area and drag, but it could also increase pressure on the chest and shoulders and complicate breathing and visibility. The fairing design thus became a negotiation between aerodynamics and ergonomics. Where is the rider most exposed to the oncoming air, and how can a shell provide relief without becoming intrusive? This line of thinking helped push the innovation beyond mere shielding into an integrated architecture that supported both performance and rider welfare.

It is important to emphasize that there was no single inventor or model that can be named as the first motorcycle with a fairing. The evidence points to a period when racing teams began to test detachable front panels and partial shells during the 1950s and 1960s, as part of a broader push toward aerodynamic efficiency in Grand Prix contexts. These early experiments were necessarily incremental. They relied on the willingness of teams to trial, observe, and iterate. A simple windshield or a small nose cone could demonstrate meaningful gains in speed or stability, and over time such fragments of fairing philosophy coalesced into more comprehensive shell shapes that could cover substantial portions of the bike’s frame and, in some configurations, extend to the sides and under the belly. The transition from racing experiment to production reality was gradual. Once the performance benefits were demonstrated on the track, manufacturers began to translate those gains into sport-focused street machines. The production fairing, with its more polished lines and refined integration, reflected a new standard: air is not just something to be endured; it is part of the machine’s design envelope, a factor to be optimized rather than ignored.

The broader implications of these aerodynamic advances extend beyond top speed. A well-executed fairing changes the character of the machine. It alters airflow around the rider’s torso, reduces fatigue by shielding the torso and arms from constant wind pressure, and can improve the bike’s balance at high speeds by shaping the way air interacts with the front end. The rider’s visibility and the ease of instrumentation access are also affected, guiding how dashboards and controls are laid out within the cockpit. The fairing’s influence thus becomes a synthesis of engineering discipline and human factors engineering. It is about making speed sustainable, and about turning raw mechanical power into a more controllable, livable experience for the rider over long distances and through demanding conditions.

As this transformation matured, the fairing ceased to be a mere cover and began to serve as a defining aesthetic and functional signature of modern sport motorcycles. The shift from lightweight, modular front shields to integrated, full-coverage shells reflected evolving priorities: the pursuit of maximum aerodynamic efficiency, the need for rider protection against the environment and debris, and the pursuit of a cohesive design language that communicates performance. The late 20th century saw fairings becoming almost universal on performance-oriented machines, as the technology that had proven its worth in racing contexts descended into the broader market. The lineage connects back to those early experiments, where a simple concept—shielding the rider from air—grew into a sophisticated package of shape, materials, and engineering that shapes how motorcycles move through air today.

For readers tracing the arc from first ideas to mature technology, a compact takeaway emerges. The first motorcycle fairing did not spring from a single breakthrough; it arose from a convergence of racing demands, material innovations, and an expanding understanding of aerodynamics and human factors. The desire to reduce drag, to stabilize handling at speed, and to protect and comfort the rider formed a coherent set of objectives that steered designers toward increasingly ambitious shells. The 1960s provide a crucial waypoint, a period when detachable panels and more comprehensive shells began to appear on racing bikes, signaling the transition to the modern fairing you see on sport motorcycles today. This is not merely a tale of better shapes, but a story about how engineering, rider experience, and race culture interacted to reshape a machine’s entire silhouette.

The chapter of this history that follows—how these aerodynamic ideas moved from race tracks into production models and into the everyday rider’s hands—rests on the premise established by those early experiments. The fairing, once a reaction to wind and fatigue, became a deliberate instrument of performance, safety, and ergonomics. It invited riders to push beyond what they previously believed possible, inviting both the rider and the machine to participate in a refined dialogue with the air. In that conversation, the first fairing stands as a milestone: not a singular invention, but a beginning—a practical answer to a complex problem that would forever alter the look, feel, and capability of motorcycles.

For further reading on the broader history of how fairings evolved, you can explore related discussions in the fairings collection, which offers a sense of how modern configurations relate to the early experiments described here. See the broader range in the fairings collection.

External resource:

A more authoritative historical perspective is available at https://www.motocycle.com/history-of-motorcycle-fairings/.

A Velvet Frontier: How the First Motorcycle Fairing Rewrote Speed, Stability, and the Race Itself

The first sight of a motorcycle fairing is not a single moment of sudden triumph but a quiet shift in how engineers and riders imagined the road. Before fairings, motorcycles moved through air as a stubborn obstacle to momentum, their exposed frames and rider silhouettes writing drag into the very heart of performance. Riders learned to fight the wind with position and grit, but as speeds climbed, the wind fought back with a burden that reduced efficiency, tested endurance, and taxed the senses. The emergence of the first deliberate, purpose built fairings did not arrive with a fanfare. It arrived as an engineering solution born from a need to ride farther, faster, and more comfortably on a machine whose mechanical heart beat with accelerating tempo. In this sense, the earliest fairings were not merely cosmetic shells; they were a basic acknowledgment that air is a vehicle’s most influential adversary at speed. The evolution from open frame practicality to a protective aerodynamic envelope marks a turning point in racing history, a moment when speed was no longer constrained only by engine power but by the craft of shaping air itself around moving metal and rider.

What followed was a gradual, highly iterative process. Designers began with modest plates and modest aims, placing simple wind deflectors at the front to shield the hands and chest from buffeting and to smooth the approach to oncoming air. The goal was twofold: reduce drag and coax the air into a more predictable path along the bike’s contours. As competition intensified and speeds crept toward astonishing thresholds, those early deflectors evolved into more integrated shells. The late 1950s and early 1960s saw the rise of full fairings that enveloped the front end of the motorcycle and extended into the sides, creating a continuous air channel around the rider. This shift toward a complete body shape was the birth of the modern concept of aerodynamic efficiency within motorcycle design. It is tempting to think of the fairing as a single invention, a spark that lit a new era; in truth, it was a chorus, a collaborative effort across many workshops and racing teams that recognized speed as a problem best solved through aerodynamic intuition and practical testing rather than a single stroke of genius.

In those early days, the physics of air resistance was understood well enough to matter, even if the science looked modest by today’s standards. Designers learned to think in terms of streamlined forms, reducing frontal area, guiding airflow over and around the rider, and preventing turbulent wake from spoiling stability at high speed. The impact on race performance was tangible. Riders could maintain higher speeds for longer stretches, especially on fast, straight sections of circuits, where drag and lift were most punishing. In the world of high-speed competition—the long straights and the unforgiving surfaces of revered tracks—the fairing became a strategic tool. It worked with the frame, the suspension, and the tires to shape a package whose success depended on balance as much as raw horsepower. The numbers tell a convincing story: speeds that once hovered at a lower ceiling could be sustained more steadily. The rider could remain more composed, with less thrust required to overcome wind pressure and less fatigue from the constant micro corrections demanded by buffeting. The arc of performance improvement intertwined with the aerodynamic envelope, a partnership between human skill and engineering artistry.

The fairing’s impact was not limited to the physics of forward motion. It touched rider ergonomics, protective considerations, and even race strategy. A well sculpted shell could offer more than a smoother ride; it could shield the shoulders, arms, and torso from wind pressure, enabling a rider to maintain a powerful, lean posture for longer without sacrificing control. Wind interaction also altered heat management and comfort, which in turn influenced rider endurance during grueling races and long-distance events. The shells created a new dimension of predictability: the wind’s behavior around the bike became a factor that could be anticipated, tested, and refined in wind tunnels and on the track. This dependency on aerodynamic feedback pushed teams to adopt a more systematic approach to design, treating bodywork as an integral part of the chassis rather than an afterthought. In this sense, the fairing catalyzed a broader shift toward engineering discipline in racing culture, where data, modeling, and hands-on experimentation began to converge with the craft of riding.

Material choices and manufacturing realities also chart the story of those early fairings. The first generations were often built from accessible composites and rigid laminates that could be shaped, cut, and joined with relative ease. The emphasis was on stiffness, surface quality, and the ability to reproduce a form with reasonable manufacturing effort. As racing pushed further into the realm of extreme speeds, later iterations experimented with stronger, lighter materials and more complex geometries. The evolution from simple deflector plates to full, integrated shells meant that designers had to address a broad range of concerns: structural integrity under high loads, potential for debris impact, stability across a spectrum of speeds, and even the aerodynamic consequences of mounting points, junctions, and openings for radiator and cooling. Each refinement compounded the challenge but also the opportunity. The fairing became a canvas for experimentation, an arena where theoretical aerodynamic concepts collided with the practical constraints of track time, heat, and vibration. The result was a lineage of forms that, while diverse in their silhouette, shared a common purpose: to merge human ambition with the science of air to transform what a rider could do on a machine.

As the decades rolled forward, the legacy of the first motorcycle fairing settled into the DNA of racing and beyond. The shell’s success demonstrated that aerodynamics was not a niche concern for elites in wind tunnels but a core facet of every fast motorcycle design. It reframed how engineers addressed the chassis, front-end geometry, and even the rider’s interface with the machine. The modern racing machine, with its contoured surfaces and carefully integrated wings or vents, owes a debt to those early experiments that proved air could be tamed with intention. The fairing helped shift racing strategy as well. Teams began to plan for efficient aerodynamics along the entire course of a lap, recognizing that high speed was not merely a matter of peak horsepower but of maintaining a favorable power-to-drag ratio, minimizing energy expenditure on upstream sections to carry advantage into the later stages of a race. In the broader scope of motorcycle design, aerodynamic efficiency also permeated street-oriented models, where comfort and fuel economy can improve when wind resistance is thoughtfully managed. The fairing, once a feature of competitive machines, gradually became a feature of the sport’s culture — an enduring reminder that speed, safety, and rider welfare grow together when air is respected as a design partner rather than an adversary.

The narrative of the first fairing is a reminder that innovations rarely arrive as singular thunderclaps; they arrive as a chorus of small, persistent improvements that accumulate into a new standard. It is tempting to look for heroic moments or immediate revolutions, but the history of fairings reflects a patient, iterative craft. Every newly shaped line, every tested junction, and every measured improvement in boundary-layer behavior contributed to a more stable, efficient, and comfortable ride at high velocity. The fairing’s influence extended beyond the track. It shaped how engineers think about the relationship between the rider and the machine, how designers conceive protection without stifling performance, and how teams organize the workflow of test, measure, and refine. It is no stretch to say that the first practical fairing didn’t just reduce drag; it redefined what a motorcycle could be, turning air from a force to be battled into a factor to be leveraged.

For readers tracing the arc from early wind deflecting plates to the sophisticated aero packages of today, the story of the first fairing furnishes a crucial context. It shows how aerodynamic thinking injected a new logic into chassis design, how the ride quality could be elevated without compromising speed, and how racing cultures learned to read the air as a collaborator rather than a capricious element. In retrospect, the first fairing marks a cultural moment as well as an engineering one: a moment when riders and manufacturers began to treat air as part of the vehicle’s physics, a factor to be optimized in concert with power, weight, and geometry. It is this convergence between speed ambitions, rider comfort, and aerodynamic understanding that continues to define racing motorcycle design today. The shell that began as a shield against the gale became, in the hands of engineers, a shaping of future velocity, a standard against which every new form would be judged, and a continuing invitation to chase the next, more efficient silhouette on the endless roads and racing circuits that define motorcycling’s enduring magnetism.

Wings on the Ride: The Rise of Motorcycle Fairings

In the early years, motorcycle fairings grew from practical wind protection and simple shields built in makerspaces. Designers sought relief from wind, weather, and fatigue while preserving visibility and control. Over time wind tunnel testing and race experience pushed fairings toward purpose-built aerodynamics that improved front end stability and rider comfort. By the 1960s through the 1980s production models adopted integrated front ends, modular panels, and lighter composites, turning fairings into a standard feature across sport, touring, and everyday bikes. Today fairings serve performance and personalization, reflecting a shared engineering lineage where air is guided to support speed, comfort, and rider confidence.

From Exposed Frames to Aerodynamic Form: The Birth of the First Motorcycle Fairing and the Rise of Modern Bike Design

Riders once rode with the landscape as a constant companion. The wind pressed against jackets, helmets, and the rider’s own body, while the machine pressed forward with little interruption beyond the noise and heat of the engine. In that era, motorcycles looked almost like open frames suspended on two wheels, their silhouettes dictated more by function than by form. The idea of a fairing—the hard shell that would envelope the machine and cocoon the rider in a more controlled aerodynamic environment—emerged not as a sudden invention but as a natural response to a growing tension between speed, efficiency, and rider comfort. If one asks when the first fairing arrived, the honest answer is not a single, gallery-worthy moment but a gradual shift. Designers and engineers, responding to the demands of higher speeds and longer rides, began to test coverings that could smooth airflow around the rider and the bike alike. These early efforts were modest: rudimentary shields, partial cowls, and simple plates tucked into the front or sides of the machine. They were not yet the integrated, sculpted forms we associate with modern sport and touring bikes. Still, they represented a decisive departure from the unprotected frame, a pivot that framed a new engineering problem: how to choreograph air rather than ignore it.

The mid-20th century marks the watershed where these ideas crystallized into what we recognize today as the modern fairing. In the 1930s and 1940s, as motorcycles tasted higher speeds on open roads and in the crucible of racing, the value of reducing wind resistance became clearer. The design world began to look at the rider and the machine as a single aerodynamic entity, a pairing whose cooperation would determine how quickly and efficiently the bike could move. The early solutions, though still evolutions of primitive concepts, started to address a few core questions: how to shield the rider from the buffeting and noise of wind at speed, how to protect vital components from dirt, rain, and debris, and how to manage the separation of turbulent air that tends to destabilize a vehicle at speed. These questions pushed designers to rethink the geometry of the front of the bike and the way the bodywork could guide air smoothly around the rider’s form and then back into the slipstream.

What followed was not a revolution in a single stroke but a steady, disciplined program of experimentation. The fairing proved to be more than an aesthetic shell; it was a calculated engineering response to real, measurable needs. By streamlining the rider and machine’s profile, the fairing reduced aerodynamic drag, a factor that becomes increasingly consequential as speed climbs. Drag reduction translates directly into practical gains: higher top speeds, better fuel efficiency, and improved stability in wind gusts. The rider benefits too—less fatigue, more comfortable posture, and reduced wind pressure on the chest and helmet. In a broader sense, the fairing reframed how engineers defined performance. Speed was no longer a matter of raw power alone; it depended equally on how the machine moved through air, how that motion interacted with the rider’s body, and how the entire system stayed balanced under a range of atmospheric conditions.

In racing circles, the fairing’s impact was immediate and pronounced. A more aerodynamic church built around the rider’s cockpit meant faster laps, steadier cornering at high speeds, and a more predictable relationship between throttle input and the bike’s response. The science of air channels, airflow lines, and streamlined surfaces began to permeate the design ethos of competition machines. The result was a feedback loop: teams that embraced aerodynamics achieved measurable gains, which in turn encouraged production builders to translate these successes into road-legal machines. The boundary between race engineering and consumer technology softened as design language migrated from the track to the showroom. A glossier, more cohesive silhouette emerged, one that balanced wind deflection, rider protection, and the visual grammar of speed. This transition did not erase the practical concerns of durability and maintenance; instead, it integrated them into a more holistic approach to motorcycle engineering. The fairing’s function expanded beyond reducing drag to include routing cables and wires, shielding vulnerable components, and shaping the engine’s cooling airflow. The bike no longer existed as a bare mechanical skeleton; it became a system, a carefully arranged set of shapes that worked together to optimize performance in a real-world environment.

As the decades rolled forward, the early achievements in aerodynamics rippled across the spectrum of motorcycle design. The adoption of more integrated bodywork gradually became standard practice, and the fairing ceased to be a mere accessory and began to define the character of entire categories. Sportbikes adopted sleek, all-enveloping shells designed to minimize drag and maximize stability at frighteningly high speeds. Touring machines, long associated with comfort and endurance, adopted fairings that offered both protection from the elements and a controlled air environment to ease the rider’s long-distance journey. The shaping of the front end—how the nose interacted with air, where ridges and curves guided flow, how air would reattach smoothly onto the bike’s surface after passing the rider—became a constant conversation among designers. The language of aerodynamics widened beyond simple drag reduction to considerations of lift, downforce, and vortex behavior. Engineers learned that even subtle changes to the fairing’s contours could alter steering feel, front-end weight distribution, and overall balance. This realization led to new tools and methods, from wind tunnel testing to computational fluid dynamics, that made the fairing not only more efficient but also more predictable and tunable. In essence, the first fairing catalyzed a shift toward a design philosophy where speed and efficiency are inseparable from how a machine meets the air it travels through.

The cultural and technical implications extended far beyond the track. The modern bike, now shaped with a sense of purpose for wind and weather, became a platform that rewarded precision in form as much as power in the engine. The rider’s experience—feeling the wind, hearing the siren-like whistle of air as it interacts with the body, noticing how the bike lunges forward when the throttle opens—became a dialogue between human and machine conducted through engineering. This conversation fed back into production practice. Where once a motorcycle might have been treated as a utility with occasional cosmetic refinements, the era of the fairing anchored aerodynamics as a central design discipline. It encouraged the layering of features intended to maximize airflow management without compromising access to service points or rider visibility. The result was a repertoire of design strategies—safer, more efficient, and visually expressive—that would shape the look and feel of motorcycles for generations.

To trace the lineage of these ideas is less about listing a sequence of models and more about understanding a shared trajectory. The 1950s and 1960s, particularly in regions known for fast, competitive two-wheeled engineering, saw the fairing evolve from a protective shield to a purposeful envelope that actively sculpted the air that met the machine. The innovations that emerged during this period did not stop at the front of the bike. They influenced the overall silhouette, the transitions between panels, and the way the tail end managed wake. Riders and teams demanded a calmer, more efficient ride at high speeds, and designers responded with increasingly cohesive surface architecture. The modern motorcycle, with its integrated bodywork, multi-panel surfaces, and careful attention to the rider’s line of sight and posture, is the living outcome of that early ambition to tame air. The fairing, once a practical necessity, became a defining element of the machine’s identity and capability—a symbol of how ingenuity can translate abstract principles of physics into tangible riding experiences.

As readers who are engaged with the evolution of motorcycle design, we can appreciate that the first fairing did not merely add a shield to a frame. It initiated a design revolution that taught engineers to think of a bike as an aerodynamic system with a rider at its center. The modern aerodynamic language—the runway of curves and angles that define contemporary sport and touring bikes—has its roots in the early experiments and the iterative improvements that followed. Today’s machines, with their sculpted noses, integrated panels, and even aerodynamic appendages like winglets and subtle vortex generators, owe a debt to those foundational efforts. The fairing’s legacy is evident not only in race results or mile-per-mile efficiency but in the broader discipline it introduced: the idea that speed, safety, and rider comfort can be coaxed from air through thoughtful, precise shaping. The first fairing did not declare itself as the ultimate solution; it opened a path toward a design philosophy that continues to guide innovation in motorcycle engineering.

For readers who wish to explore a contemporary, industry-facing perspective on how fairings are perceived today, a look at the broader ecosystem of bodywork and its availability through specialized collections can offer a practical sense of how far the concept has evolved. A useful entry point is the Honda fairings collection, which showcases how modern bodywork continues to blend protection with performance and aesthetics. Honda fairings collection demonstrates how the principles that emerged with the first fairing persist in today’s market—airflow management, rider comfort, and the pursuit of a unified, efficient silhouette that speaks to both speed and endurance.

External resource for further reading on the aerodynamic history of fairings and its influence on motorcycle design can be found here: https://www.motorcycle.com/motorcycle-design-history-fairings-aerodynamics/.

Final thoughts

The evolution of the motorcycle fairing not only showcases the advancements in engineering and design but also highlights the relentless pursuit of improved performance and rider safety. From rudimentary designs meant to shield riders from the wind to sophisticated structures enhancing aerodynamics, the fairing has become indispensable in modern motorcycle manufacturing. As we continue to embrace innovation in motorcycle design, the foundational work laid by early fairing designs will guide future developments, ensuring that both aesthetics and functionality remain at the forefront of the motorcycle industry.